The partisan spin cycle was in full-effect following this week‘s midterm elections. President Obama did his best to frame the Republican victories as an expression of economic discontent rather than an outright rebuke of his legislative agenda. Needless to say, the opposition party interpreted the results a little differently. Conservatives, in fact, were eager to tout Tuesday’s outcomes as a mandate to roll back Obama administration’s most visible policies. Or, as soon-to-be Speaker Boehner said on Wednesday, “It’s pretty clear the American people want a smaller, less costly and more accountable government.”

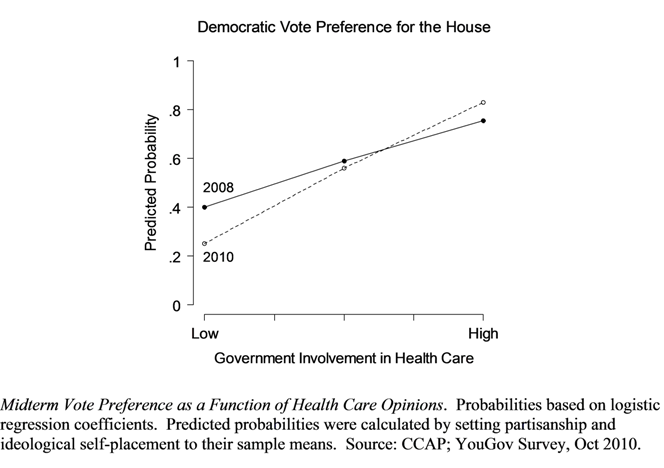

That contention appears to be difficult to argue with. The exit polls showed that a plurality of voters (48 percent) want to repeal the recently passed health care legislation, with nearly everyone in that group supporting Republican candidates for the House of Representatives. Analyses of YouGov survey data would seem to provide even greater evidence in support of this popular claim that Democrats took a “shellacking” in large part because their policies were out of step with the preferences of the American mainstream. Indeed, the figure below shows that after controlling for partisan and ideological considerations, attitudes about the government’s involvement in health care were a significantly stronger predictor of respondents’ vote intentions in an October 2010 survey than they were of reported vote choices for the House of Representatives in the 2008 Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project (CCAP)—a YouGov survey of 20,000 respondents conducted by political scientists, Simon Jackman and Lynn Vavreck. Moreover, and consistent with many post-election assertions about how liberal legislation hurt Democrats at the ballot booth, the display suggests that the plurality of Americans who want only minimal government involvement in health care were substantially more supportive of Republicans in 2010 than they were just two years earlier.

Pundits and politicians who are interpreting the midterms as a referendum on Obama’s agenda, however, would be wise to read the forthcoming book of MIT political scientist, Gabriel Lenz. Lenz convincingly demonstrates that policies subjected to intense public debate rarely become more important determinants of citizens’ vote choices. Instead, voters will more often first pick a candidate based upon partisan and performance factors and then adopt that politician’s views about high-profile policies. So, for example, voters who decided to vote for Republican candidates in the midterms because of the poor economy would also be more likely to embrace that party’s position on health care reform.

Some preliminary evidence suggests that this reverse causality phenomenon in which vote choice causes policy positions rather than policy preferences motivating votes is responsible for the greater impact of 2010 health care attitudes shown above. Many of the CCAP respondents who we re-interviewed during last fall’s contentious debate over health care reform changed their health care opinions from early 2008 to late 2009. There was a clear pattern found in this opinion change too: Obama voters became more supportive of government involvement over time while McCain voters increasingly wanted health care to be left up to individuals. Only a few of these respondents, however, changed their support for Obama to comport with their previously recorded health care attitudes. It certainly appears from these results, then, that the popularity of the president and his party was not dependent on strong sentiments against government involvement in health care. Rather, support for the Democrats’ health care plan seems to be dictated by Americans’ underlying partisan preferences.

The underlying distribution of partisan preferences in national elections, of course, is largely based on performance factors like the state of the economy. To be sure, health care could have easily factored into performance evaluations of both Obama and Democrats in congress. Many voters, for instance, undoubtedly found it misguided to focus resources on passing health care reform legislation when so many Americans are facing such severe economic hardships. That is a far cry, however, from the Republican leadership’s matter of fact claims about how they won the House because the outgoing Congress’s agenda did not reflect the ideological preferences of the American mainstream.