Much has been written lately about the caustic nature of the Republican candidates for the presidential nomination. Whether we take Frank Rich’s account of the “Molotov Party” or the Economist’s more subtle nudge asking “Is the Middle Missing?” the consensus seems to be that the Republican party – at least at the elite level – is ideologically extreme.

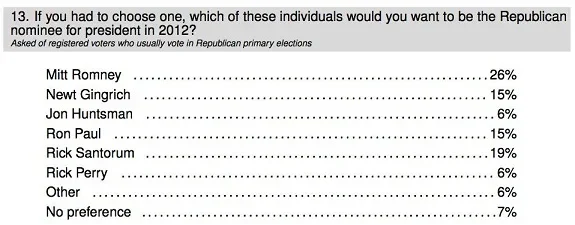

Republican voters have been characterized the same way. Over and over again, pundits pointed out that Mitt Romney’s support was capped at 25% nationally because conservative Republicans preferred “anyone but Romney.” Indeed, most polling results, including our own YouGov results from January 7-10, 2012 (below), showed Romney’s support to be “stuck” at a quarter of the Republican electorate.

Twenty-five percent might seem like a small share, and it would be in a two-person contest; but in a seven-person race, 25% is actually quite good. By way of comparison, consider that in 2008 during the same week that our survey ran (January 7-10) Mike Huckabee was at 25% in a Gallup Poll, riding momentum from his win in Iowa. The eventual nominee -- John McCain -- was polling at 19%. Ahead of McCain was the focal candidate of the season, Rudy Giuliani, who came in at 20%. There were eight candidates in the field at this point in 2008, and none of the “frontrunners” had any more support than Romney does now. No one in 2008 argued that the party was searching for the anti-Huckabee or anti-Giuliani. It was just a crowded field.

Why is the number of alternates important? Because many people are conflating two very different things: support for a candidate and disdain for another. Just because a voter prefers Rick Santorum for the Republican nomination does not mean that this voter would prefer any other candidate on the ballot to Romney. This false premise has led to a lot of faulty conclusions about Romney’s support among the electorate.

In fact, Romney is the second choice of a quarter of the electorate who did not rank him as a first choice. Nearly 40% of Gingrich voters list Romney as their second choice. More than half of Huntsman voters do so.

This suggests that as the field narrows, Romney’s support will grow, in contrast to the notion that the “anti-Romney” vote could coalesce around another, apparently more conservative candidate if there weren’t so many conservatives in the race.

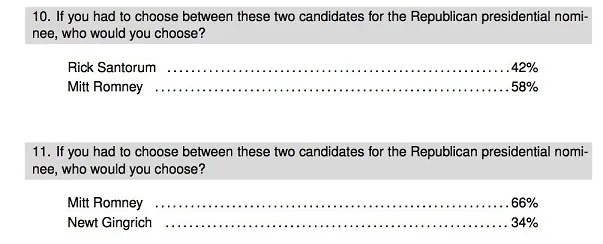

To assess how Romney would fare if there really were only one other conservative in the race, we put the two-person choice to a representative sample of the electorate in the same YouGov poll fielded the first week of January. In these hypothetical races, Romney actually does much better than he does in the field of six candidates that exists today. Against Santorum, Romney wins 58% of the vote. Against Gingrich he wins a whopping 66%.

It simply is not the case that a vote for someone other than Romney is a vote against Romney. As the field narrows, a Romney nomination becomes more inevitable, not less.