“Everyone is entitled to his own opinions,” Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously said, “but not to his own facts.” Unfortunately, a decade of political science has demonstrated that, when it comes to politics, the line between facts and opinions is often blurred and occasionally obliterated. The current election season provides some prime examples.

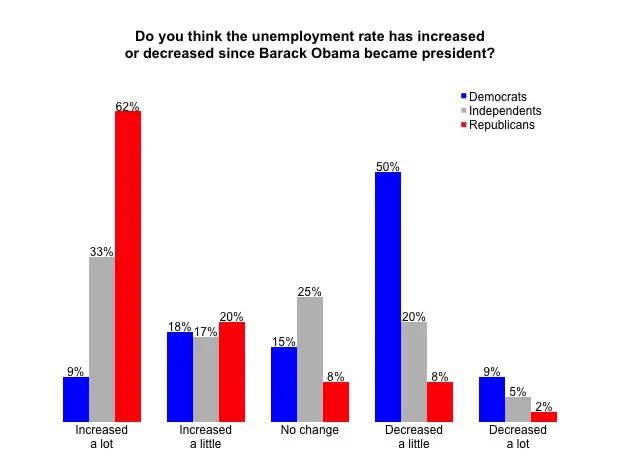

Consider: “Do you think the unemployment rate has increased or decreased since Barack Obama became president?”

That seems like a pretty straightforward factual question, but Americans’ answers are all over the map. Almost one-third of the 1000 respondents in a recent YouGov survey said that unemployment has “increased a lot” since the president took office, while a similar number said that it had “decreased a little” or even “decreased a lot.” (What do you think? The correct answer appears below.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, much of this variation in beliefs is attributable to partisan biases. More than 60% of Republicans said that unemployment has increased a lot, while almost as many Democrats said that it has decreased. In both cases, their beliefs were conveniently consistent with their party loyalties.

However, even among the minority of survey respondents with no partisan axe to grind—so-called “pure” independents—there was substantial variation in beliefs, with 45% saying that unemployment has increased, 24% saying that it has decreased, and 31% saying that it has stayed the same. And those differing beliefs are politically consequential: 57% of the second group, but only 20% of the first group, said they approved of Obama’s performance as president.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate at the time of the survey was 8.3%—a little higher than the 7.8% rate in January 2009, the month President Obama was inaugurated. However, less than one-fifth of the respondents in the YouGov survey correctly said that unemployment has “increased a little” during Obama’s time in office. Even with partial credit for those who said that the unemployment rate has “remained the same” (since the rate in February 2009—just a month after Obama took office—was 8.3%, just as it is now), two-thirds of the respondents were wrong about one of the most salient economic (and political) facts of the past four years.

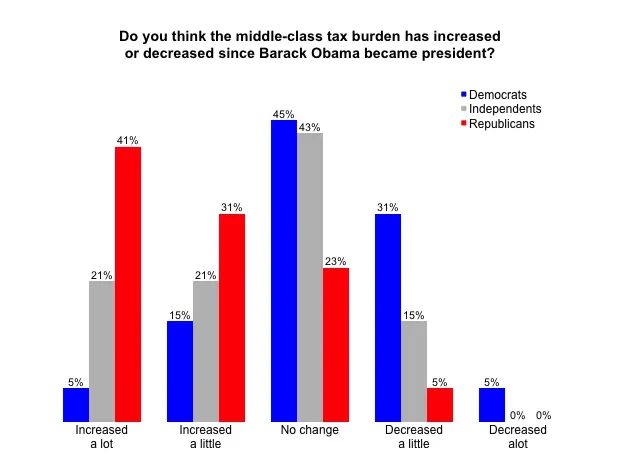

Here’s another question: “Do you think the tax burden on middle-class Americans has increased or decreased since Barack Obama became president?”

Here, too, people’s beliefs differ greatly, with more than 40% saying that taxes have increased, about 20% saying that they have decreased, and almost 40% saying that the middle-class tax burden has remained unchanged. Again, the disagreement is largely along partisan lines, with more than 70% of Republicans but less than 20% of Democrats saying that the tax burden has increased.

The correct answer to this question is that the tax burden on middle-class Americans has decreased during Obama’s presidency. More than one-third of the 2009 stimulus bill consisted of tax cuts, including expanded tax credits for workers, people with children, college students, homebuyers, and the unemployed. In 2010, Obama proposed and Congress accepted a substantial temporary reduction in the payroll tax, which was recently extended through 2012. Meanwhile, the Bush-era income tax cuts were also extended through 2012. While one might quibble about whether all of this amounts to decreasing the tax burden on middle-class Americans by “a little” or “a lot,” only 20% of the public gave either of those answers.

As with perceptions of unemployment, perceptions of how the tax burden has changed during Obama’s years in office have significant political ramifications. Among “pure” independents (those who do not lean toward either party), Obama’s job approval rating was 52% among those who recognized that the tax burden had decreased, but only 35% among those who thought it was unchanged—and only 17% among those who (wrongly) thought it had increased.

Unfortunately, misperceptions of basic facts are not easily corrected—especially in the setting of a political campaign, where every claim is subject to partisan dispute. Moreover, many of the judgments voters are called upon to make are much less straightforward than these purely factual questions about unemployment and tax rates. Should the president be able to keep gas prices low, or are they beyond his control? In the former case, it may make sense to punish President Obama at the polls for pain at the pump; but in the latter case that would be no more sensible than kicking the dog after a hard day at work.

As it happens, Americans are split on that question, too, with 47% saying the president should be able to keep gas prices low and 37% saying they are beyond his control. (71% of Republicans, but only 25% of Democrats, said that the president should be able to keep gas prices low.)

We often think of election outcomes as collective verdicts on the state of the nation under the incumbent president. As political scientist Morris Fiorina put it long ago, “In order to ascertain whether the incumbents have performed poorly or well, citizens need only calculate the changes in their own welfare.” Are we better off now than we were four years ago?

What happens, then, if citizens are not really up to calculating “changes in their own welfare”—if our judgments about even the most salient and straightforward aspects of our collective well-being are based more on partisan biases and media buzz than on reality? In that case, the “rough justice” Fiorina claimed to discern in election outcomes will be very rough indeed.