Race has recently taken center stage in the presidential campaign. From Joe Biden’s suggestion that a Romney-Ryan presidency would re-enslave African-Americans, to some liberal commentators’ contentions that the Romney campaign is using racial code words like “welfare” and “anger” to mobilize anti-black sentiments against President Obama, charges and counter-charges of playing the race card now abound.

Part of this racialized turn in the campaign involves Romney’s welfare ad earlier this month—an ad that questionably accused Obama of ending welfare for work requirements. While that charge may seem race-neutral, there is a long-standing and strong association in white Americans’ minds between welfare and “undeserving” African-Americans (see here and here). According to Jonathan Chait, then, “the political punch of this messaging derives from the fact that white middle-class Americans understand messages about redistribution from the hard-working middle-class to the lazy underclass in highly racialized terms.” An extensive body of social science research described as racial priming seems to support Chait’s contention. That research shows that such code words as “welfare” and “inner-city,” especially when combined with racial imagery (e.g., the hardworking whites in Romney’s ad), can make racial attitudes a more central determinant of political evaluations (see: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). One might therefore expect the welfare ad to activate racial attitudes in public opinion.

We can test that expectation thanks to some unique experimental data collected last week by YouGov. The survey randomly assigned half of its 1,000 respondents to view the Romney welfare ad (see above) while the remaining half of the sample did not see the ad. Respondents then answered a series of questions to discern whether and how the ad affected their opinions. Unfortunately, these follow-up questions did not include vote choice or candidate favorability, which were asked earlier in the survey. We did, however, ask respondents how well Mitt Romney and Barack Obama’s policies would benefit the following groups in society: the poor, the middle class, the wealthy, African-Americans and white Americans. Answers were then recoded to range from 0 (“hurt them a great deal”) to 100 (“help them a great deal”).

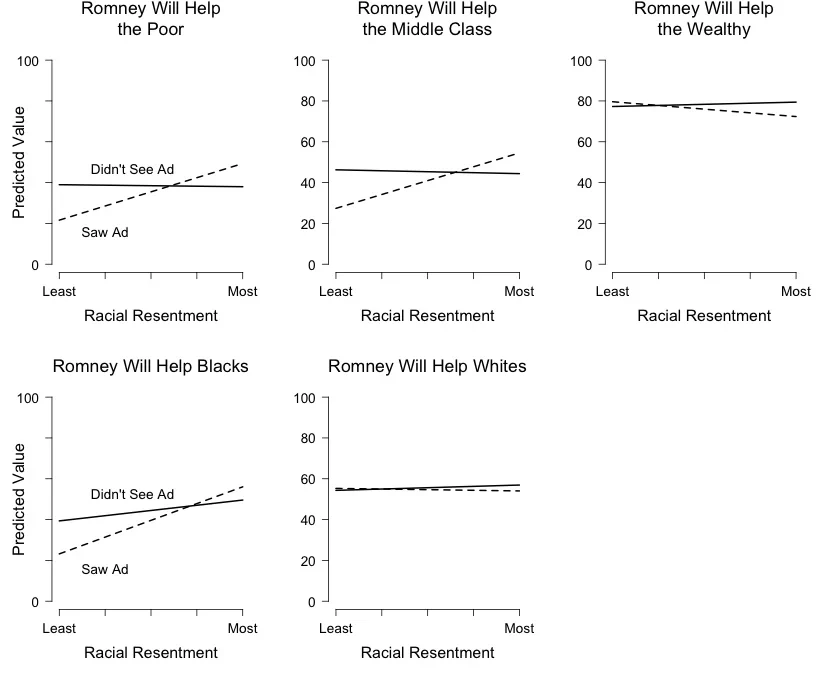

The welfare ad did not appear to affect people’s overall answers to those questions. However, it did make attitudes toward blacks a stronger predictor of respondents' views about the consequences of Romney’s policies for the poor, the middle class, and African-Americans. To measure attitudes toward blacks, we use a scale called “racial resentment” in the scholarly literature. For respondents to this survey, we actually assessed racial resentment much earlier, when these respondents were first interviewed in a December 2011 survey. The four questions that make up this measure are here.

The figure below shows that there was almost no relationship between racial resentment and the opinions of people who did not see the ad. But among those who saw it, racial resentment affected whether people thought Romney will help the poor, the middle class, and African-Americans. Moreover, seeing the ad did not activate other attitudes, such as party or ideological self-identification. It only primed racial resentment.

(Note: Predicted values were calculated from OLS coefficients by setting partisanship, ideology, and race to their sample means. Source: YouGov Survey, August 2012)

At the same time, the ad failed to “racialize” views of whether Romney’s policies would benefit whites and the wealthy. This likely stems from the fact that Romney favorability ratings are strongly related to thinking his policies will help the poor, the middle class, and blacks, but only weakly related to believing he’d help whites and the wealthy.

Interestingly, the ad did not appear to further racialize the perceived consequences of Obama’s policies, either. This is probably because racial attitudes are already linked to Obama, and a single political ad isn’t enough to significantly strengthen an already strong relationship.

Nevertheless, the results from our experiment suggest that ads like the one in this post may well contribute to the growing polarization of public opinion by racial attitudes beyond the voting booth in the age of Obama.

[I thank Brendan Nyhan for suggesting a study of this topic, and John Sides and Lynn Vavreck for help in designing the survey questions.]