When the September jobs report showed that unemployment had dropped to an unexpectedly low 7.8%, former General Electric CEO Jack Welch helped launch a new conspiracy theory when he tweeted: "Unbelievable jobs numbers..these Chicago guys will do anything..can't debate so change numbers." Even though the unemployment statistics are produced by the respected and politically insulated Bureau of Labor Statistics, Welch's theory was disseminated by numerous conservative pundits and amplified by a wave of irresponsible media coverage. As we approach Election Day, it's worth taking a look back and assessing the damage.

To assess the prevalence of conspiracy theory beliefs about manipulation of the unemployment data, I contributed several questions to a YouGov poll conducted October 27-29, 2012 (margin of error: +/- 4.6%; topline data and sample demographics here). The poll was conducted before the October unemployment figures were released last Friday and thus reflects public beliefs about the September unemployment data approximately three weeks after its release on October 5.

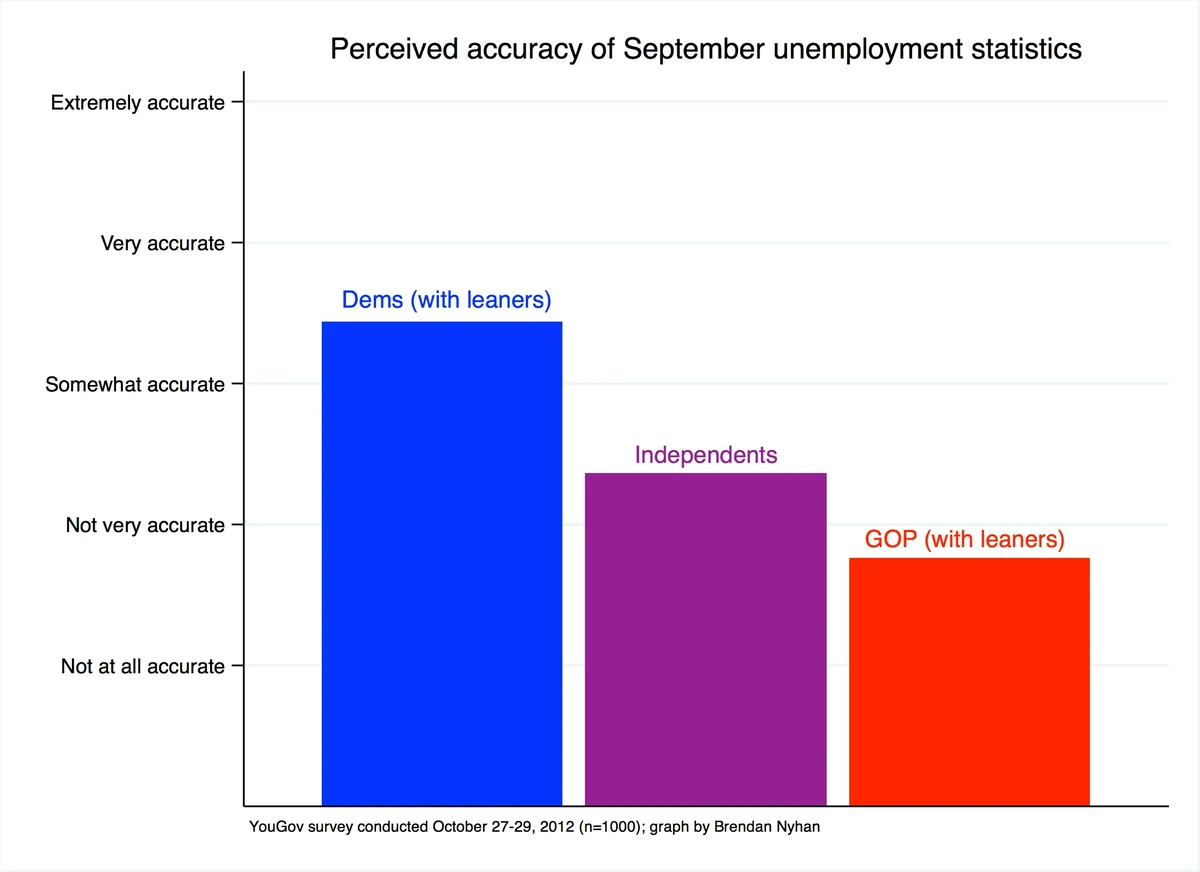

I first asked survey respondents how accurate they believe the 7.8% unemployment figure is on a five-point scale from "Extremely accurate" to "Not at all accurate." The median response was the middle category of "Somewhat accurate," which may reflect skepticism about the way unemployment figures are calculated or a general distrust of government. However, there was a steep partisan gradient in mean responses by party. When we separate Democrats (including independents who lean Democrat), Republicans (including leaners), and true independents, we find that independents and especially Republicans are far less likely than Democrats to believe that the unemployment statistics are accurate:

In particular, more than 70% of respondents reported having heard about the claim that the unemployment statistics were manipulated for political reasons (21% said they had heard a lot about it, 51% said they had heard a little, and 28% said nothing at all). Half said they had first heard about the claim on television and 20% from news websites or blogs, suggesting the role played by the mainstream media in circulating the claim (only 5% said they first heard about it on a social networking site like Facebook or Twitter).

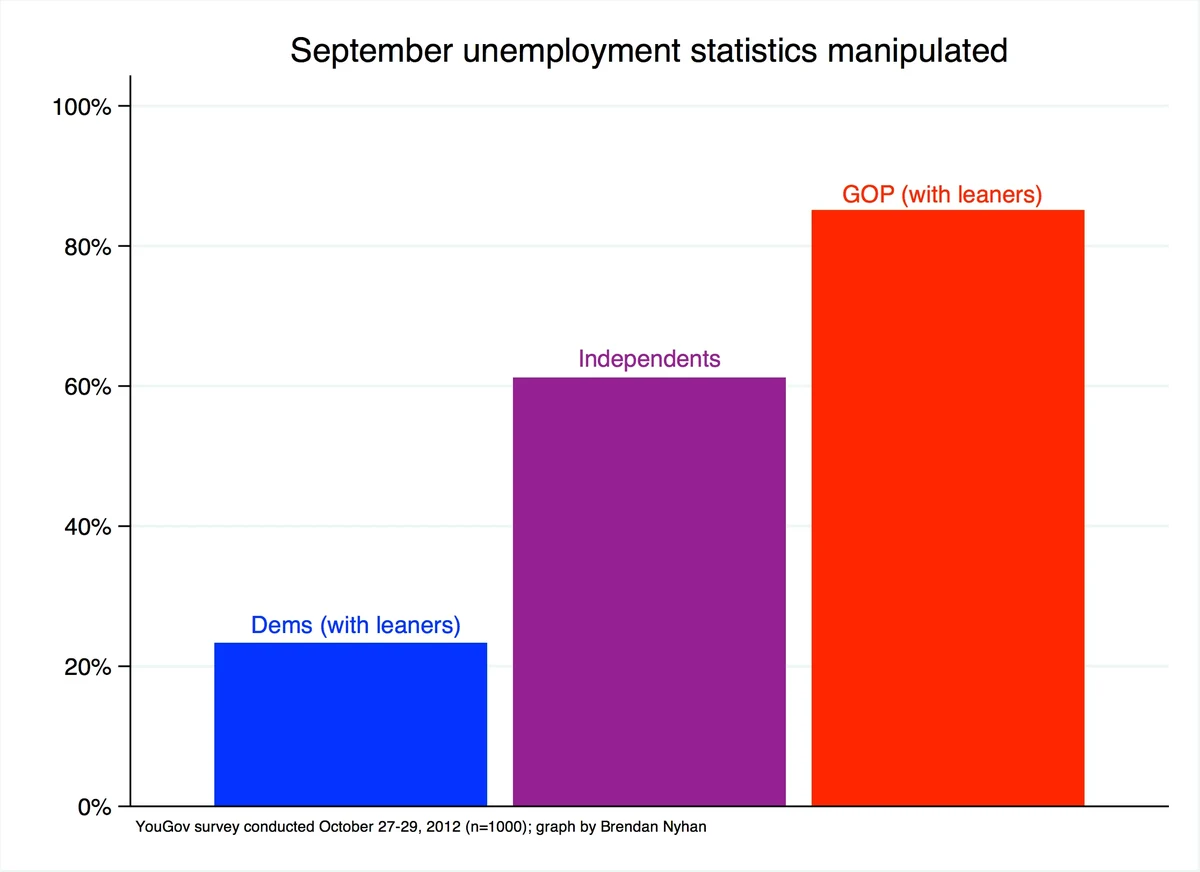

Moreover, a disturbing number of respondents endorsed the unemployment statistics conspiracy theory. When I explicitly asked respondents whether the September figure had been manipulated for political reasons or had been calculated correctly, 55% said they thought the figures had been manipulated. In this case, the partisan gradient was even steeper than on the perceived accuracy question - only 23% of Democrats thought the figures were manipulated compared with 61% of independents and a staggering 85% of Republicans:

While we cannot determine the origins of these beliefs in a single survey, the partisan differences we observe are consistent with extensive previous research on the importance of motivated reasoning in misperceptions about politics and the difficulty of correcting misinformation among motivated reasoners.

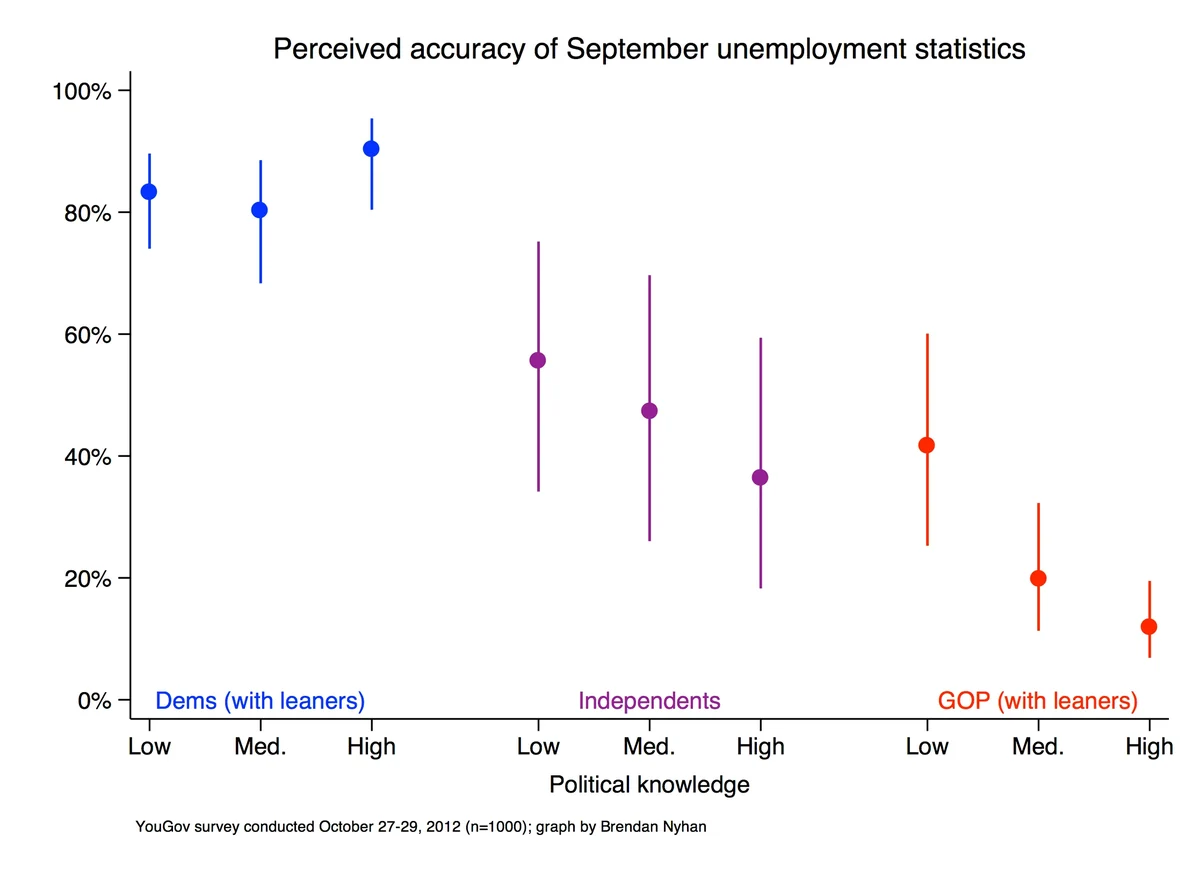

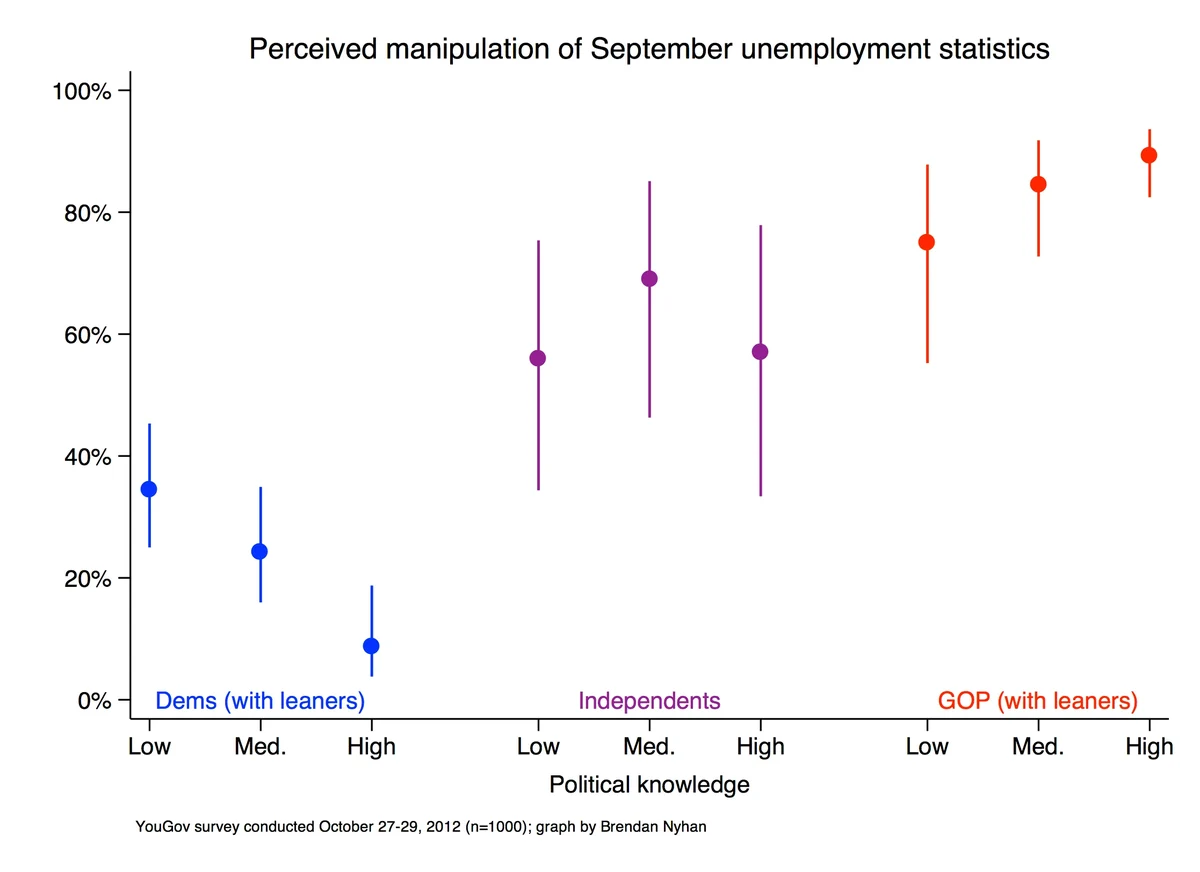

The relationship between political knowledge and conspiracy theory belief may be especially surprising to many people. It's often assumed that more knowledgeable or educated people will be less likely to believe in false or unsupported claims, but that assumption is often tenuous. The reason is that knowledge or education can often make it easier to maintain consistency between your political views and factual beliefs.

In this case, I divide the sample into terciles of low, medium, and high political knowledge based on their answers to a ten-question battery and plot the probabilities of believing the unemployment figures are at least somewhat accurate and, conversely, that they are being manipulated for each partisan group (along with 95% confidence intervals).

Among respondents who identify as Democrats or lean toward the party, high-knowledge respondents are more likely to believe the figures are accurate and less likely to believe they are being manipulated than individuals with low or medium knowledge. For Republicans (including leaners), however, respondents with high political knowledge are paradoxically less likely to believe the unemployment statistics are accurate than those with low or medium political knowledge. In addition, high knowledge Republicans are more likely to believe the statistics are being manipulated than low knowledge respondents. (The difference between medium and high knowledge respondents is not statistically significant.)

This survey was conducted just days before a presidential election - a time when partisanship is at its peak. Nevertheless, people's willingness to endorse unproven conspiracy theories is a disturbing reminder of the damage that can be inflicted on public discourse when irresponsible claims are given widespread circulation.