Neurodivergent is an umbrella term for people whose brains work in an atypical fashion. Autism, ADHD, and learning disabilities are examples of neurodivergent conditions or identities. However, there isn’t a formalized list of what diagnoses or identities are considered neurodivergent. Neurotypical is an umbrella term for people whose brains work in alignment with social norms.

One-third of Americans (32%) know what the term neurodivergent means without it being previously defined, according to a recent YouGov poll. A majority of Americans (56%) weren’t sure how to define the term. One respondent said neurodivergence means “a person whose brain processes stimuli differently than what’s typical.” Another person defined neurodivergent to mean that “the world isn’t built for us so we struggle. We need hacks and work-arounds. The basics of life take more effort. We need more rest and down time or we burn out.”

54% of respondents who have been diagnosed with or believe they are autistic and 61% of respondents who have been diagnosed or believe they have ADHD are able to define neurodivergent.

After being provided the definition ("Neurodivergent is an umbrella term for people whose brains work in an atypical fashion. Autism, ADHD, and learning disabilities are examples of neurodivergent conditions or identities."), 19% of Americans say they are neurodivergent. 72% of Americans said they are not neurodivergent — or, that is, neurotypical.

26% of respondents who say they are neurodivergent when given the definition are unable to define the term without that prompt. 24% of respondents who say they are neurotypical say they know how to define neurodivergent without being given the definition.

A greater share of young Americans identify as neurodivergent than the share of older Americans who do. 30% of adults under 30 identify as neurodivergent but only 6% of Americans 65 and older do.

A significantly greater share of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people — as well as those who say their sexual orientation is "other" — than of straight people identify as neurodivergent (46% vs. 15%). Additionally, more Democrats (23%) than Republicans (13%) identify as neurodivergent — and more Democrats than Republicans identify as neurodivergent within each age group.

Some of the diagnoses associated with neurodiversity include ADHD, dyspraxia, OCD, and more. Majorities of Americans have not heard of dyspraxia (a neurological coordination and developmental disorder), dysgraphia (a learning disorder consisting of limited fine motor and language processing skills), dyscalculia (a specific learning disorder that impacts a person’s ability to interpret numbers), Meares-Irlen Syndrome (a perceptual processing disorder), misophonia (where certain sounds can be physically and emotionally painful and prompt a flight response), rejection sensitive dysphoria, or RSD (emotional and physical pain caused by criticism, often associated with ADHD), and synesthesia (when a brain continuously conflates two or more sensory responses).

One-fifth of Americans have been diagnosed (7%) or have self-diagnosed (13%) themselves with ADHD.

While only 2% of respondents said they’ve been diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum, 10% of Americans believe they are autistic. Women and non-binary Americans historically have been excluded from studies on Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), meaning that autistic women and non-binary Americans frequently go misdiagnosed or undiagnosed. The same historical and medical bias in autism diagnoses and studies applies to Black Americans and other Americans of color. One-quarter of Black Americans (25%) say they had never heard of ASD, compared to 13% of white Americans.

Neurodiversity is different ways of experiencing the world — not just a diagnosis. Additionally, biases in medical studies and the larger health care industry mean that some of these conditions are under-diagnosed. However, there are many traits and behaviors associated with neurodiversity or diagnoses associated with neurodivergence.

Sensory triggers can be overwhelming to some neurodivergent Americans — particularly those formally or self-diagnosed with a sensory processing disorder or misophonia. 5% of Americans say that they are always angered by certain noises or textures.

One type of synesthesia is sound-to-color synesthesia, where certain sounds cause a person to see colors or shapes. 9% of Americans say they usually or always associate words or sounds with colors.

Hyper-empathy, or the ability to overwhelmingly physically or emotionally feel the emotions of others, is a common trait among autistic people. However, as ASD is a spectrum, some autistic people have limited cognitive empathy. 20% of Americans say they feel a fictional character’s emotions — a form of hyperempathy. About half of Americans (53%) say that they are much or somewhat more empathetic than other people. 10% of Americans say that they are much or somewhat less empathetic than others.

The ability to focus — and on what — differentiates types of neurodivergences. One-fifth (21%) of Americans say that their ability to focus on something that interests them is much better than others' — a concept known as hyperfocus or hyperfixation and can be common for autistic people and some people with ADHD and AuDHD. 40% say it is about average and 7% say it is worse than others'. 69% of Americans say they always or usually pay very close attention to detail. However, only 14% of Americans say that their ability to focus on something that doesn't interest them is better than others. One-third of Americans (32%) say it is worse.

18% of Americans say they find it always or often hard to focus on one thing at a time. One-quarter of Americans say they often start a new task before finishing an old one. These traits or behaviors can be common for people with ADHD.

Neurodiversity can be associated with limited motor skills and coordination, such as with dysgraphia and dyspraxia. 12% of Americans say they always or usually bump into things around them.

28% of Americans say that they always or usually feel like their brain works differently from everyone else. One-third of Americans (32%) say that they sometimes feel like their brain works differently from other people.

Neurodivergence is an identity and larger community, like some of the traits that often fit within it — such as being autistic. Just because someone has a diagnosis or thinks they should have a diagnosis doesn’t mean they identify with the neurodiverse community. 27% of Americans who say they have been diagnosed or believe they should be diagnosed with ADHD say they are not neurodivergent. 63% say they are. 49% of Americans with OCD say they are not neurodivergent. 40% say they are.

19% of U.S. adult citizens identify as neurodiverse, but the true percentage may be higher. 14% of Americans say that they believe between 10% and 20% of Americans are neurodivergent. Another 14% of Americans say that 20% to 30% of Americans are neurodivergent.

Nearly half of Americans (47%) know someone else who is neurodivergent. Of course, Americans may know someone who is neurodivergent without knowing they are neurodivergent. More women than men say they know someone who is neurodivergent. More women also say they have a child who is neurodivergent (11%). Adults under 30 (34%) are likelier than Americans 65 and older (9%) to have friends who are neurodivergent.

Few Americans say that representation of neurodivergent people in the media is good. Only 10% say that neurodivergent characters more often are three-dimensional; 15% say that neurodivergent characters more often are portrayed as caricatures while 29% say both treatments happen equally often and 46% are unsure.

More Americans say that neurodivergent characters are underrepresented than say they are equally represented, in each form of media asked about: reality TV (32% vs. 17%), film (32% vs. 21%), TV dramas (31% vs. 21%), TV comedies (28% vs. 23%), books (27% vs. 23%), comics or graphic novels (24% vs. 19%), and true crime (24% vs. 19%).

In 1973, the first major disability civil rights legislation was passed — Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. Section 504 made it illegal to discriminate against disabled Americans in federal buildings or federally-funded organizations. The Jimmy Carter Administration refused to implement the law, resulting in the formation of the Disability Rights Movement and Section 504 protests — hundreds of disabled Americans and the Black Panthers held sit-ins in Health, Education, and Welfare buildings across the country for 26 days until the law was implemented. 25% of Americans have heard about Section 504 or 504 plans, a type of school disability accommodation based on the law.

12% of Americans have heard about the oldest law asked about — Bell v. Buck. Buck is a Supreme Court ruling from 1927 holding that disabled Americans can be forcibly sterilized without their consent. The justices' majority decision (8-1) said that “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Buck never has been overturned and has since become codified law.

The U.S. disability law that the most Americans know about (78%) is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which provides a variety of rights and protections from discrimination for disabled Americans. 43% of Americans have heard about Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs, which is a legal document providing individualized educational instruction and a case worker for disabled students. These were created with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Each of the diagnoses associated with neurodivergence included in this survey are defined as a disability under all of these laws. However, not everyone who identifies as neurodivergent identifies as disabled.

This year, Representative Robert Garcia — a California Democrat — introduced a resolution recognizing the importance and contributions of neurodivergent people to the U.S., calling for U.S. society to be inclusive of neurodivergent Americans and to strive towards interdependence, and condemning discrimination of neurodivergent people. 65% of Americans — including 78% of Democrats and 61% of Republicans — say they would support this resolution passing. More Americans who identify as neurodivergent support the resolution (75%) than do people who do not identify as such (63%).

According to some scholars, disability justice advocates, intersectional activists, and neurodiversity equity advocates, neurodivergent Americans don’t currently have equal rights under U.S. law. Bell v. Buck is still the law of the land. Employers are allowed to pay neurodivergent Americans below minimum wage. Parental rights can be terminated solely on the basis of a parent being neurodivergent or disabled.

The State Department promotes a vision in which disabled and neurodivergent people have the same rights against discrimination and “full participation in society” as all other people. The State Department also acknowledges that these rights are frequently violated.

13% of Americans say that neurodivergent Americans don’t currently have equal rights in the U.S.; 58% say they do. Slightly more neurodivergent Americans and Americans who know someone who is neurodivergent say that neurodivergent people don’t have equal rights than do neurotypical Americans.

Note: This article does not capitalize autism and autistic, following the AP Stylebook as articles on this website generally do, though many autistic people prefer that the words be capitalized. This article also uses identity-first language, as preferred by most in the autism community, though some autistic people and their families prefer person first language.

— Taylor Orth contributed to this article

Related:

- What Americans think about the diversity of their elected officials

- Pride and heritage months: How much do Americans know about them?

- Voting-rights reform: Broad support for many of the failed bill’s measures

- Many Americans think certain groups not protected by employment discrimination laws should be

- Views of 40 social movements reveal groups supported most by Americans

See the results for this YouGov poll

Methodology: The poll was conducted online among 1,148 U.S. adult citizens from July 10 - 12, 2024. A random sample (stratified by gender, age, race, education, geographic region, and voter registration) was selected from the 2019 American Community Survey. The sample was weighted according to gender, age, race, education, 2020 election turnout and presidential vote, baseline party identification, and current voter registration status. Demographic weighting targets come from the 2019 American Community Survey. Baseline party identification is the respondent’s most recent answer given prior to November 1, 2022, and is weighted to the estimated distribution at that time (33% Democratic, 31% Republican). The margin of error for the overall sample is approximately 3.5%.

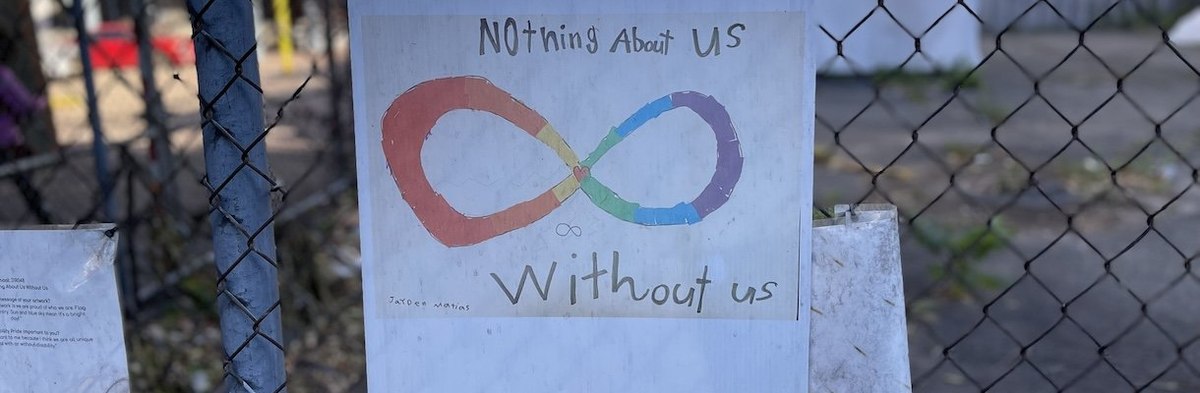

Image: YouGov (Carl Bialik / Staff)