Most voters won't support someone they don't like – and it goes both ways.

The themes advertised for the first two nights of the Republican National Convention were “Make America Safe Again” and “Make America Work Again”, but judging from the content of the speeches given a single, shared banner would have been more appropriate: Stop Hillary.

While it’s not clear this is an intentional strategy, the data suggests it is a questionable one.

To be sure, Hillary Clinton’s negatives, while historically high, remain slightly lower than Donald Trump’s. But the gap has already closed quite a bit. In fact, among registered voters, a group that has always been a bit less favorable to Clinton than the general population, Clinton is at 59% unfavorable, according to YouGov/Economist Polls conducted in July. Trump is at 61%. Given how historically bad this is – for both candidates – it’s hard to see how it could even get much worse given the way partisan voters tend to feel about their presidential candidates.

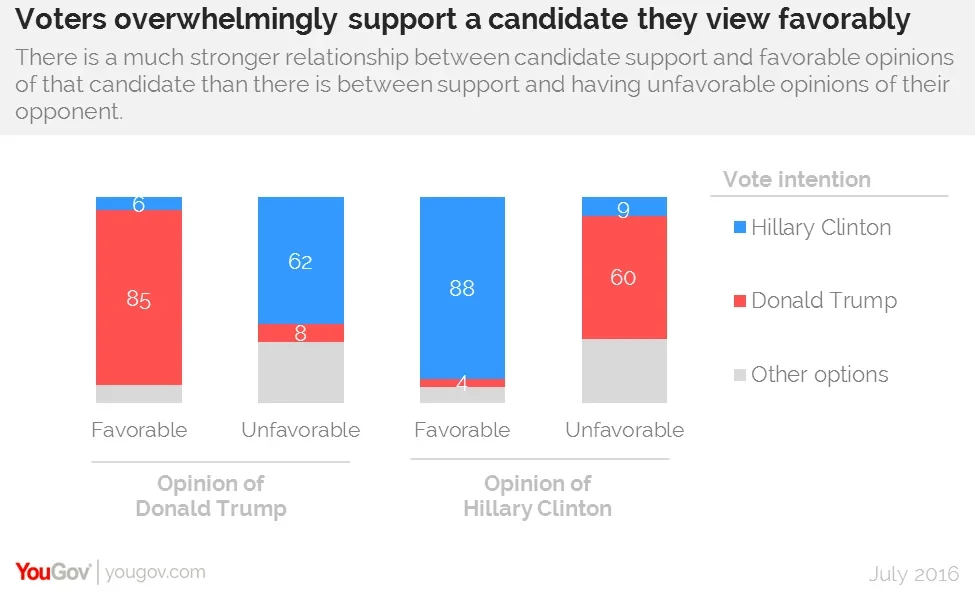

More importantly, voters who have a favorable opinion of Trump are far more likely to support him when they are asked about their 2016 vote than are people who have an unfavorable opinion of Clinton. Indeed, nearly 9 in 10 voters with a favorable opinion of Trump back him in a match up with Clinton, while just 6 in 10 with an unfavorable opinion of Clinton do the same. These ratios have been remarkably stable for months; in April it was 89% and 64%.

The same lesson goes for Clinton, who will be formally nominated at the Democratic National Convention next week, and whose supporters may be tempted to focus on tearing her opponent down instead of improving perceptions of Clinton.

In many ways this is pretty unsurprising. There is only one option if you want to show your appreciation for a candidate when heading to the ballot box: voting for them. If you dislike a candidate, on the other hand, there are technically several options, including supporting one of their multiple opponents, staying in the undecided camp, or not voting at all.

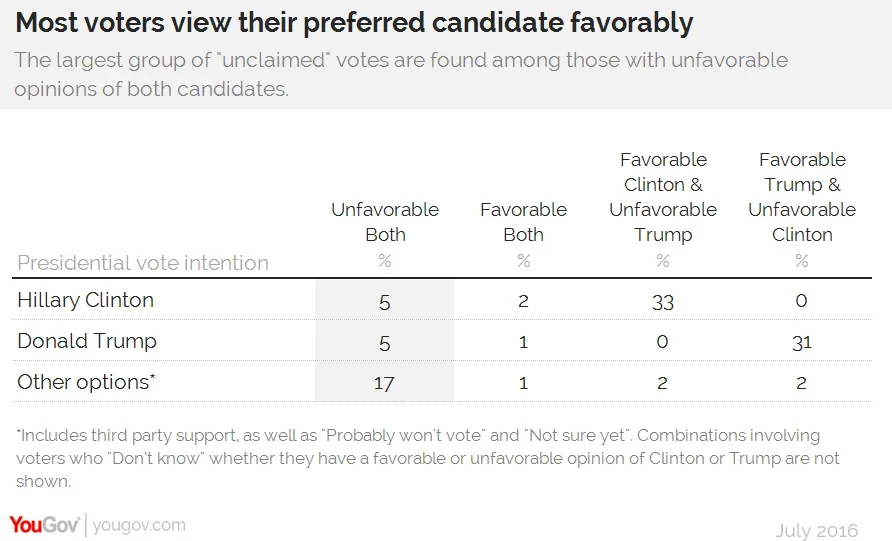

This thinking becomes even clearer when you break voters down into overlapping groups: those who dislike both candidates, those who like both candidates, and those who like one but not the other.

If you are Trump or Clinton, there simply are not very many votes to be had in the category of voters who “like you and your opponent” – because there are so few of those voters – or in the category of voters who “like you and dislike your opponent” – because virtually all of those voters already support you.

Where are the votes? In the unusually large group of voters who already dislike both candidates. Within this group, Clinton and Trump are tied, but less than half of these voters currently support either candidate.

While it’s true that, for example, Trump could win over some of these voters by making them dislike Clinton even more than him, perhaps with chants of “lock her up”. But doing so could just as easily push the voter into the “Neither” column, whereas making them see a more likeable side of Trump – something his campaign has states a goal for the convention – would put them in a category of voters far more likely to support him over his opponent.