Before Donald Trump entered politics, there was a time when Republicans thought Russia was a major U.S. enemy and Democrats were less convinced.

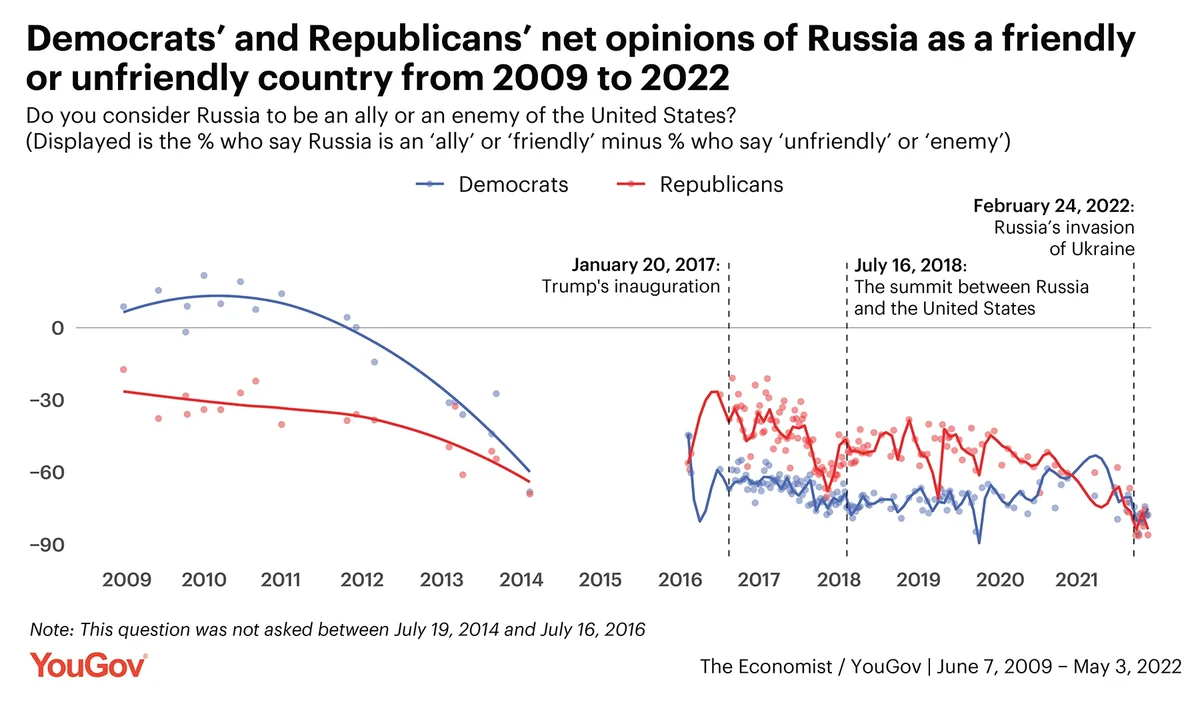

During Barack Obama’s first term as president, Democrats were more inclined to view Russia as friendly than Republicans were. Democrats had criticized Obama’s predecessor in the White House, George W. Bush, for increasing tension with Russia President Vladimir Putin, and promoted Obama’s so-called reset of Russian relations in his 2012 re-election campaign.

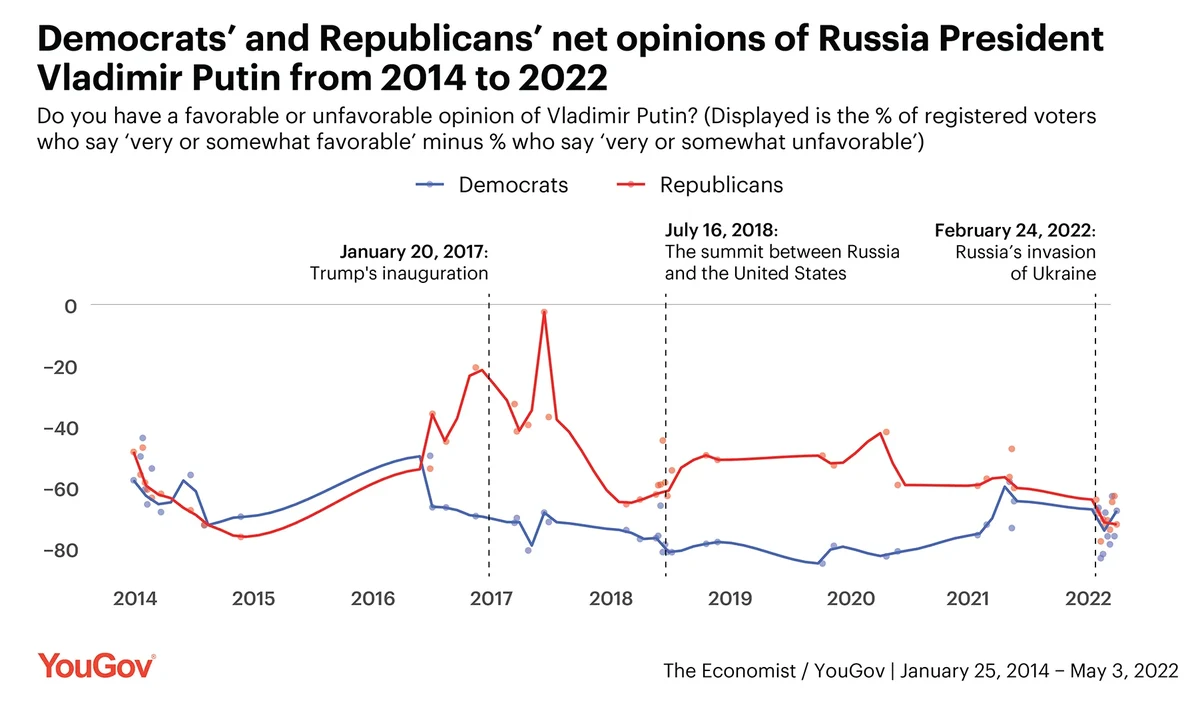

By 2014, after Russia invaded Crimea and before Trump announced his presidential bid, most Republicans (as well as most Democrats) held unfavorable views of Putin. That changed dramatically during the Trump years when Putin’s standing rose among Republicans and fell even further among Democrats. The split narrowed after Joe Biden took office, however, and Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine has largely closed the gap between Democrats and Republicans over Putin and Russia.

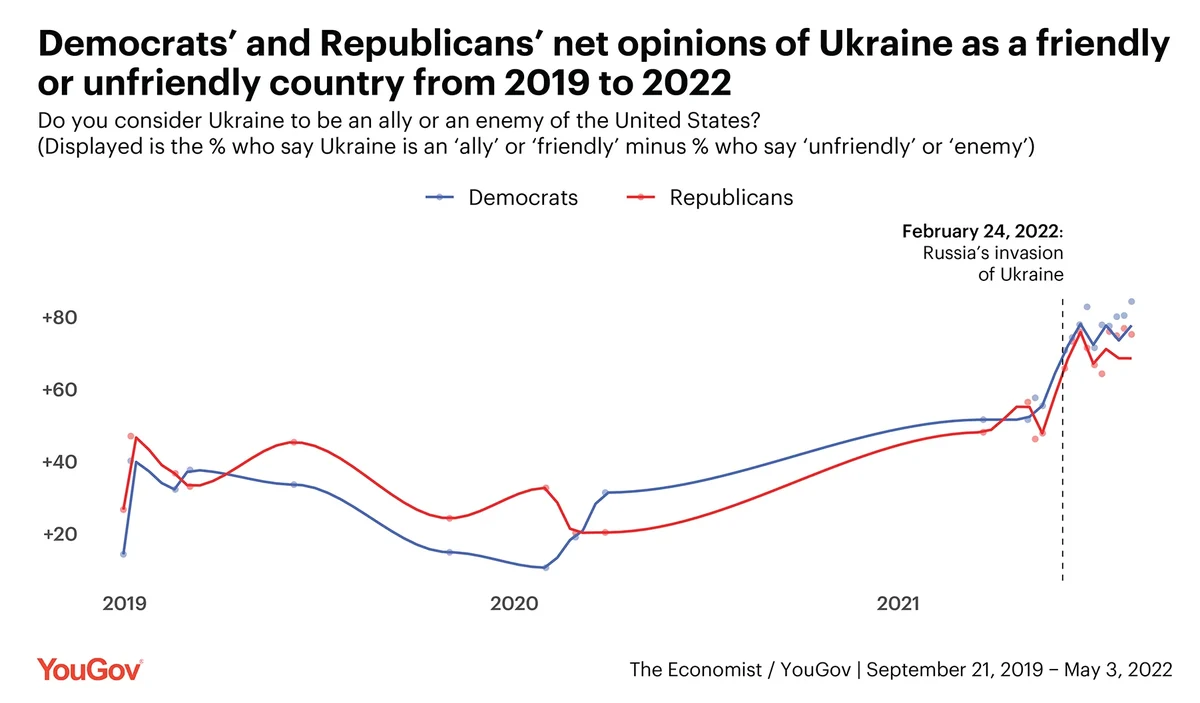

The Economist/YouGov poll has tracked Democrats’ and Republicans’ opinion regarding Russia and Putin for years: asking whether Russia is a friend or foe in more than 150 of the weekly polls since June 2009, and how favorably people view Putin nearly 50 times since January 2014. Net measures of opinion on Russia and Putin — the difference in share of people seeing the country or its leader in a positive light, compared to the share seeing the entity in a negative light – show how sharply members of the two major parties have diverged during the last dozen years. Opinion has fluctuated alongside Russia’s actions, which party controlled the White House, and how the president engaged with Putin. Less frequent polling about Ukraine and its president, Volodymyr Zelensky, shows its rapid rise toward ally status and his assumption of the anti-Putin role — with agreement among most members of both parties.

In 2014, Democrats had a net -41 view of Russia's relationship with the U.S., meaning the share of Democrats viewing Russia as an ally or friendly was 41 percentage points lower than the share who saw Russia as unfriendly or an enemy. Republicans, though, had a -50 score of Russia’s friendliness. The parties switched places on this measure a few times until 2016.

Similarly, Putin’s net score was nearly identical with Democrats (-55) and with Republicans (-54). At the start of 2014, Putin invaded Ukraine with the goal of seizing control of the Crimea peninsula while warning Western nations against getting involved. Putin’s favorability plummeted even further during the year among both Democrats and Republicans as he reclaimed Crimea and reshaped eastern Ukraine.For the next year and a half, Republicans and Democrats were generally in agreement about Putin. In an Economist/YouGov poll conducted July 23 - 24, 2016, his net score was -48 with Democrats and -53 among Republicans. And the share of Republicans saying Russia was an ally or friendly was 57 percentage points lower than the share calling it unfriendly or an enemy, compared to a -43 score among Democrats.

A few days after that poll closed, Trump said during a news conference, “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing,” referencing the emails of his Democratic opponent in the presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Net favorability of Putin jumped 25 points among Republicans that week, while dropping 6 points among Democrats. Similar shifts in partisan views of Russia in just a week flipped the parties, such that Republicans were seeing Russia more positively than Democrats. Republicans reached their highest net favorable rating of Putin (-10) in December 2016, and of Russia in February 2017.

There were some ups and downs during the Trump years in how Republicans regarded Putin and Russia. Their opinion of him went down during the Robert Mueller investigation into Russian election interference, then back up after the Russia–U.S. summit in 2018 and as Trump pushed the idea that Russia did not interfere in the election. Democrats’ opinion of Putin, meanwhile, became slightly more negative. At no point was Putin seen favorably by more Republicans than the share who saw him unfavorably, though the relative differences with Democrats are striking.In February, as Russia invaded Ukraine again, Republican and Democratic views of Russia and Putin almost converged. While there is still more support for Putin among Republicans, who generally see him as a stronger leader than they do Biden, their support for Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky is much higher, and comparable to Democrats’.

Support for Ukraine as a friend of the U.S. had been bipartisan before Russia’s invasion, strengthening among both parties after the invasion.When asked to describe Putin now and given a list of possible descriptions, Republicans are more likely than not — and about as likely as Democrats — to call Russia’s leader “power-hungry,” “corrupt,” and “vicious.” They’re slightly less likely than Democrats to call Putin “out of control,” “dishonest,” “crazy,” or “paranoid” — and more likely to call him “strategic” or a “strong leader.” But the commonalities between Democrats and Republicans on Putin are greater than their differences: Most members of both parties largely describe Putin in negative terms that depict him as a threat to the U.S., not a friend.

— Delia Bailey, Ian Davis, Joe Williams, and Taylor Orth contributed to this article

Methodology: The Economist survey is conducted by YouGov each week using a nationally representative sample of 1,500 U.S. adult citizens interviewed online. This sample is weighted according to gender, age, race, and education based on the 2018 American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, as well as 2016 and 2020 Presidential votes (or non-votes). Respondents were selected from YouGov’s opt-in panel to be representative of all U.S. citizens. The margin of error for a typical survey is approximately 3% for the overall sample.

Image: Getty