In 2004, Pennsylvania Rep. Patrick Toomey was the face of the conservative insurgency. An anti-taxes, anti-spending hawk, Toomey was one of many conservative upstarts who primaried a more moderate fellow Republican; in Toomey’s case, longtime Pennsylvania Sen. Arlen Specter.

The Republican president at the time, George W. Bush, sided with Specter, who ultimately won by less than 2 percentage points. After Specter switched parties in 2009 when polls showed Toomey defeating him in a primary, Toomey won the seat in 2010.1

But despite the conservative bona fides that helped Toomey get elected, he experienced backlash from the GOP after becoming one of seven Senate Republicans to join Democrats in voting to convict former President Donald Trump in his second impeachment trial.

Toomey’s transition from conservative insurgent to a pariah among certain factions of his party is not unique, though.

Sen. Mitt Romney called himself “severely conservative” during his 2012 presidential bid and planned to repeal the Affordable Care Act. But when he became a senator years later, he often bucked Trump’s agenda and twice voted to convict Trump in his impeachment trials, facing a drumbeat of criticism from Republicans in response.

To be clear, Toomey, Romney and now-ousted GOP party leader Rep. Liz Cheney have not abandoned the policy views that a decade ago flagged them as conservatives. But in the interim, Trump and his presidency may have shifted the ideological ground beneath their feet.

At first, Trump seemed like an unlikely candidate to redefine conservative politics. In 2016, he was pilloried as insufficiently conservative by some quarters of the GOP after supporting tax hikes on the wealthy and pledging to protect Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Voters didn’t think of Trump as that conservative. Senators who were widely regarded as conservatives, like Sens. Ben Sasse and Jeff Flake, said they wouldn’t vote for him.

Ultimately, Trump’s nomination and subsequent election set up a fight within the Republican Party over what the party stood for -- a fight the former president seems to have won. In fact, we found in our research both in 2016 and 2021 that Trump’s influence on the party has started to redefine what it means to be “conservative.”

If there’s any group of people who are likely to care about what terms like “conservative” and “liberal” mean, it’s political activists. These are the people who participate in politics beyond just voting: They volunteer for political campaigns, donate money, work for politicians, and in some cases, even run for office themselves. They also help define their parties in the eyes of voters and can be good barometers of shifting ideological winds, as they often influence and sometimes regulate politicians’ stances.

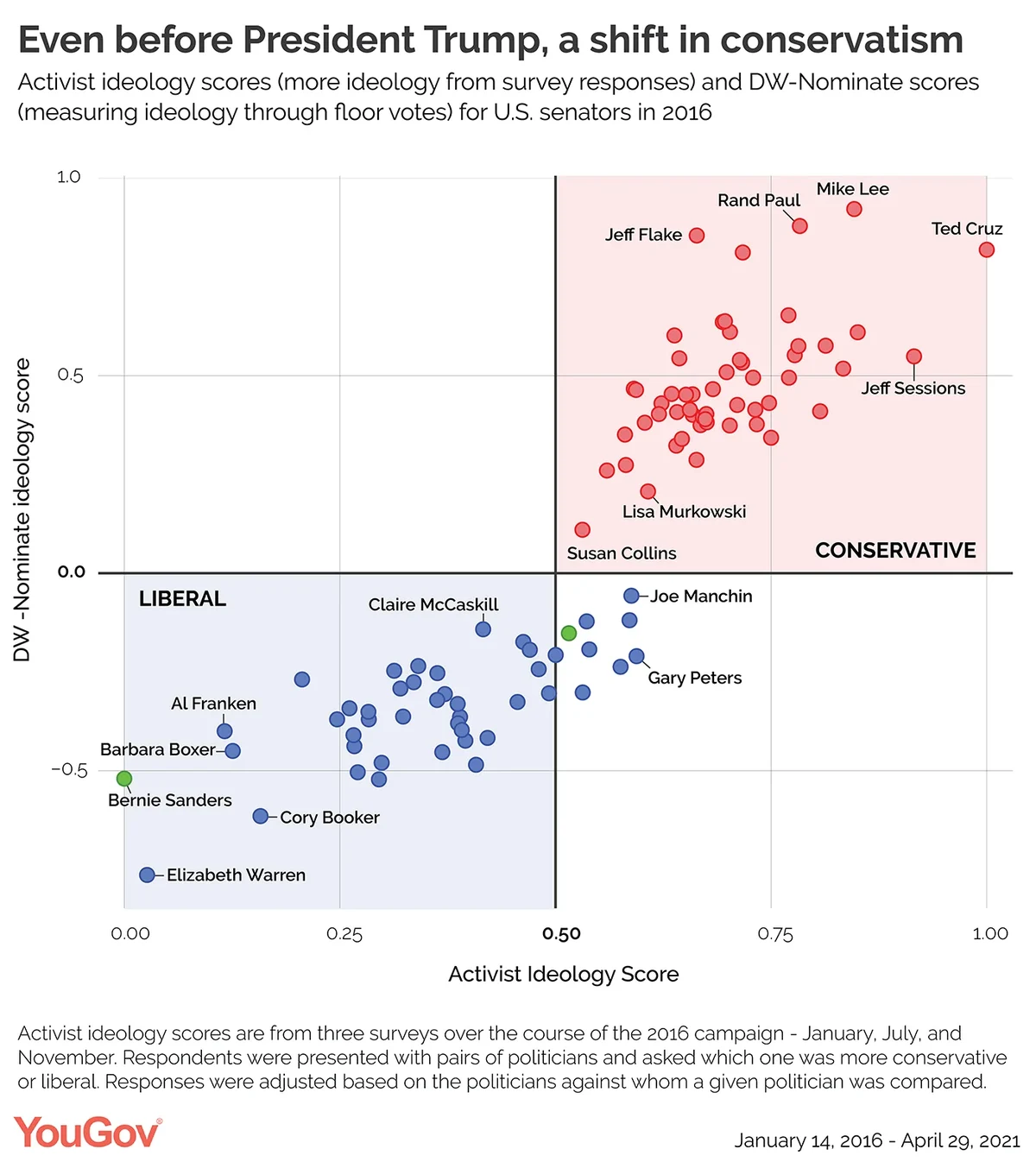

So to better understand how party activists think about conservatism and to measure Trump’s effect on how they think about it, we teamed up with HuffPost2 and YouGov to poll Republican and Democratic activists three times over the course of the 2016 campaign, and then once with YouGov in 2021 after Trump had left office, to ask them each time how conservative or liberal they thought a pair of prominent politicians was.

For each pair, we simply asked, “Which of these two politicians is more liberal/conservative?”3

By random chance, some politicians are going to be paired against especially liberal or conservative counterparts, so simply counting up the number of times a politician was graded “more liberal” or “more conservative” won’t cut it. Instead, we adjusted for the politicians against whom a given politician was compared, which is akin to a “strength of schedule” adjustment in analyzing sports teams.4

A few key findings immediately stand out. First, in looking just at our 2021 survey data, a politician’s support for Trump has come to define who party activists think of as conservative. Romney, Toomey and Sasse were all rated as fairly liberal Republicans despite their conservative voting records in Congress, according to DW-Nominate, which quantifies the ideology of every member of Congress based on roll call votes cast in a legislative session. While staunchly pro-Trump politicians (or Trump-adjacent politicians) like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, former Vice President Mike Pence, Sens. Tom Cotton, Josh Hawley and Lindsey Graham and Trump were all clustered together on the more conservative end of the spectrum, even though there is quite a bit of difference, ideologically speaking, between these men.

Pence, for instance, stands out for having established a very conservative track record pre-Trump whereas Cotton, Graham, Hawley and DeSantis’s claims to being so conservative are more closely linked to their connection to Trump. What seems to matter more, though, is not so much one’s voting record in the pre-Trump era as one’s relationship to Trump.

And despite his ideological heterodoxies, Trump was rated as more conservative than all but 10 of the 114 politicians we asked about. Ideology, in other words, isn’t just about policies.5 To be sure, this survey was fielded after the November 2020 election, the Jan. 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol and the subsequent impeachment of Trump, and so Trump may be especially influential.

However, using our survey data from 2016,6 we can see that even before Trump became president, he was starting to redefine who party activists thought was conservative.

For instance, based on their voting records via DW-Nominate, which scores voting records from 1 (most conservative) to -1 (most liberal), Flake and Sasse were about as conservative as Sen. Ted Cruz. But activists thought Flake and Sasse were significantly more moderate, quite possibly because of their outspoken opposition to Trump. Meanwhile, pro-Trump senators like Jeff Sessions (the first senator to endorse Trump) and Cotton were perceived as far more conservative than their actual voting records indicate. Trump, in other words, began to reshape who was “conservative” long before winning office.

The 2016 data also reinforce another key conclusion: unlike DW-NOMINATE, these perceived ideology scores show some Democrats to be to the right of some Republicans. That is, activists perceive there to be some ideological overlap, while estimates based on roll-calling do not. In this case, Democrats like Joe Manchin, Jon Tester, and Joe Donnelly are estimated to be to the right of Republican Susan Collins—and Tester and Donnelly are more conservative than Lisa Murkowski. Such perceptions are defensible. Manchin and Donnelly are pro-life, while Collins and Murkowski are pro-choice. Tester, meanwhile, is pro-gun rights.

A limitation of our method is that not all politicians are equally familiar, and in fact, activists declined to rate 40 percent of our 2016 pairings, saying that they didn’t know one or both senators. More unfamiliar senators tend to be ranked as more centrist. But the fact that we also observe overlap in our 2021 survey gives us confidence that this is a genuine feature of activists’ perceptions. In 2021, Utah Senator Mitt Romney joins Collins and Murkowski in being perceived as to the left of some Democrats.Of course, our measure of ideology isn’t any more “real” than a measure based on roll-call votes, but it is perhaps a closer approximation of how the country sees the ideology of these politicians. On the one hand, votes are real while talk is cheap. On the other hand, senators can only vote on the issues that are brought to the floor for a vote, and their voting decisions are often strategic. For instance, much of what they vote on is driven by party loyalty, whereas they can often express more nuance in public statements or even campaign ads. That’s why issues like abortion and a politician’s stance on it may loom large in activists’ minds, even if these issues rarely come up for votes in Congress.

Political scientists like to point out that ideology and party are not the same thing. And yet, our measure of ideology among political activists suggests it’s even trickier than we think. We know that the Republican Party is changing. Longtime conservatives like Romney and Cheney say that the party has abandoned conservative principles and that they’re holding out hope the GOP will return to them.

Our research suggests another possibility, though: Conservative principles themselves are changing. The civil war in the Republican Party, to the extent there is one, isn’t between conservatism and some new form of populism. Instead, it’s between the old view of conservatism and the new one. That suggests a very different future for the Republican Party -- one in which reactions to Trump influence who is thought of as conservative more than views on taxes or spending.

This story and additional data is also available on FiveThirtyEight.

Methodology: In four Huffington Post/YouGov surveys, Republican and Democratic activists were shown head-to-head match-ups of two prominent politicans and asked, "Which of these two politicians is more liberal/conservative?" Responses were adjusted based on the politicians against whom a given politician was compared. The four surveys were conducted January 14-20, 2016 (N=989), July 11-18, 2016 (N=972), October 28 - November 5, 2016 (N=1,068), and April 23 - 29, 2021 (N=1,110).

__________________________________________