YouGov surveyed over 8,000 voters in six countries participating in this month’s European elections, and found anti-EU and nationalist parties on the rise across the continent

On May 22nd voters across Europe will vote in elections for the European Parliament, the legislative institution of the European Union (EU).

In Great Britain, the surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) ahead of these elections has captivated the political class. UKIP formed in 1993 to oppose the UK's membership in the newly-created EU. Though this Euroskeptic (anti-EU) stance remains central to their platform, the party is also distinguished by right-wing populism and opposition to immigration.

UKIP has no representation in the British Parliament and usually places third behind the left-wing Labour Party and the governing Conservative Party when voters are asked who they will vote for in next year's general election. But in 2014 UKIP look likely to take the largest share of the vote in the upcoming European elections, potentially pushing the Conservatives into third place (behind Labour) – a first-time occurrence for that party in a nationwide poll. Due to the largely proportional allocation of representatives in the European elections, this would mean UKIP would have more seats in the European Parliament than any of Britian’s other major parties, after coming second to the Conservatives in 2009.

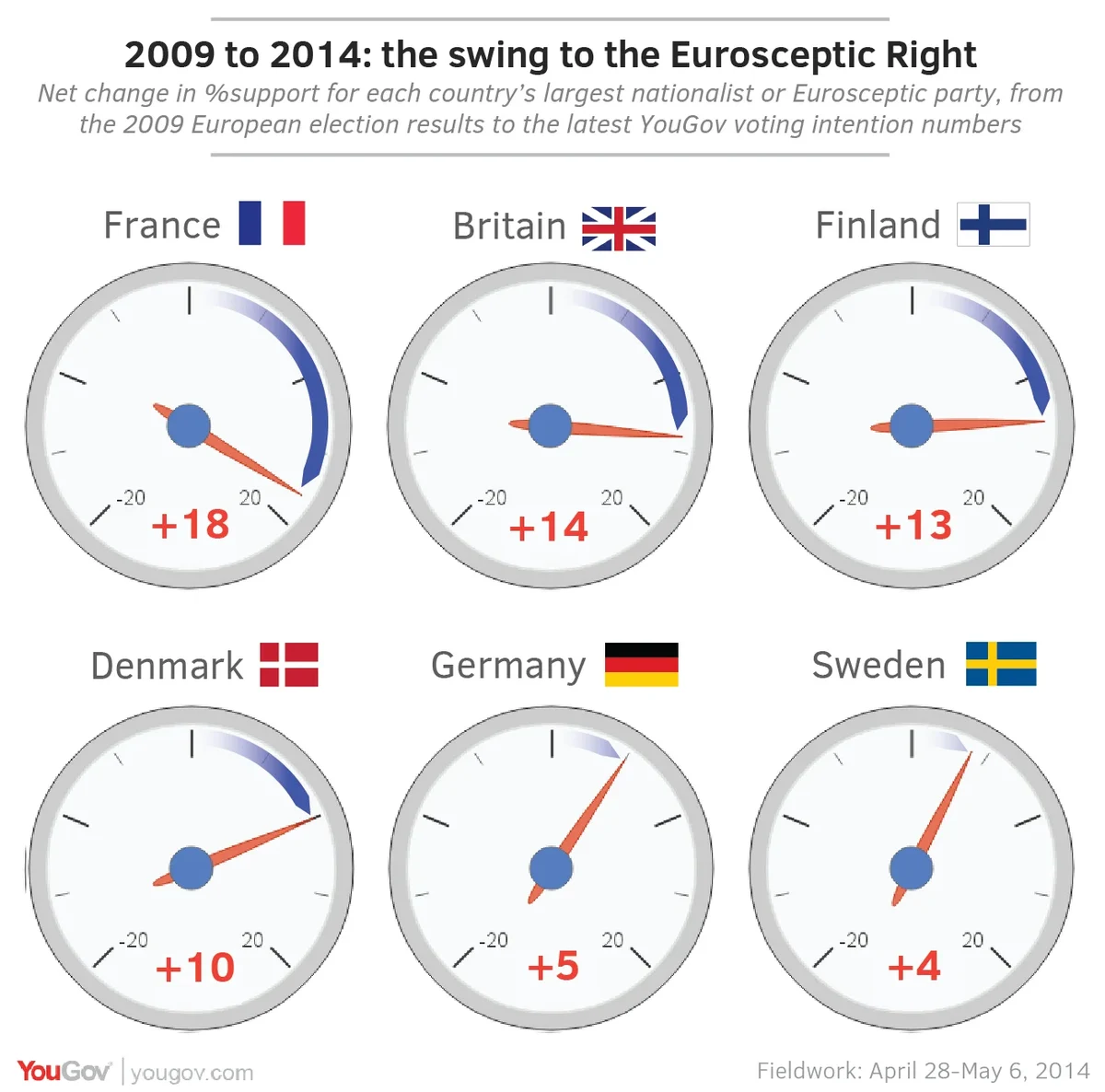

However, UKIP is far from alone among Euroskeptic parties in being likely to secure greater representation in Brussels and Strasbourg this time. In fact, as new pan-European YouGov polling can show, the main nationalist and Euroskeptic parties in all six of the countries polled have increased their support from the 2009 election results.

The graphic (above) shows the forecast increase in support since 2009 for the largest Euroskeptic party in Sweden (Sweden Democrats), Germany (Alternative for Deutschland), Britain (UKIP), Denmark (Danish People’s Party), Finland (Finns Party) and France (the Front National).

In most cases, the same party led in 2009 and leads today among Euroskeptic or nationalist parties. For Sweden, the most successful Euroskeptic party in 2009 was June List, though the Sweden Democrats were close behind. In Germany it was The Republicans (AfD formed in 2013).

The biggest swing towards an individual nationalist party in the six countries surveyed is the Front National in France. The increasingly Euroskeptic party had seen a decline in their popularity during the late 2000s, and won only 6% in the 2009 European Elections. YouGov’s latest voting intention figures have them on 24% – higher than any other party in France. Notably another Eurosceptic party, Arise the Republic (DLR), is at 2% which would match their 2009 results.

What the “swing” also doesn’t show, is that it is in Britain where a single Euroskeptic party has the greatest share of the national electorate. Nor does it account for the drop in support for the British National Party (BNP), which took 6% of the vote in 2009 but looks set to take only 1% this year. Though BNP and UKIP both support Britain leaving the EU, UKIP has gone to great lengths to distance itself from the BNP (including banning former BNP members from the party) while BNP have sought to position themselves as “genuine nationalists” and distinct from the “[Nigel] Farage regime”.

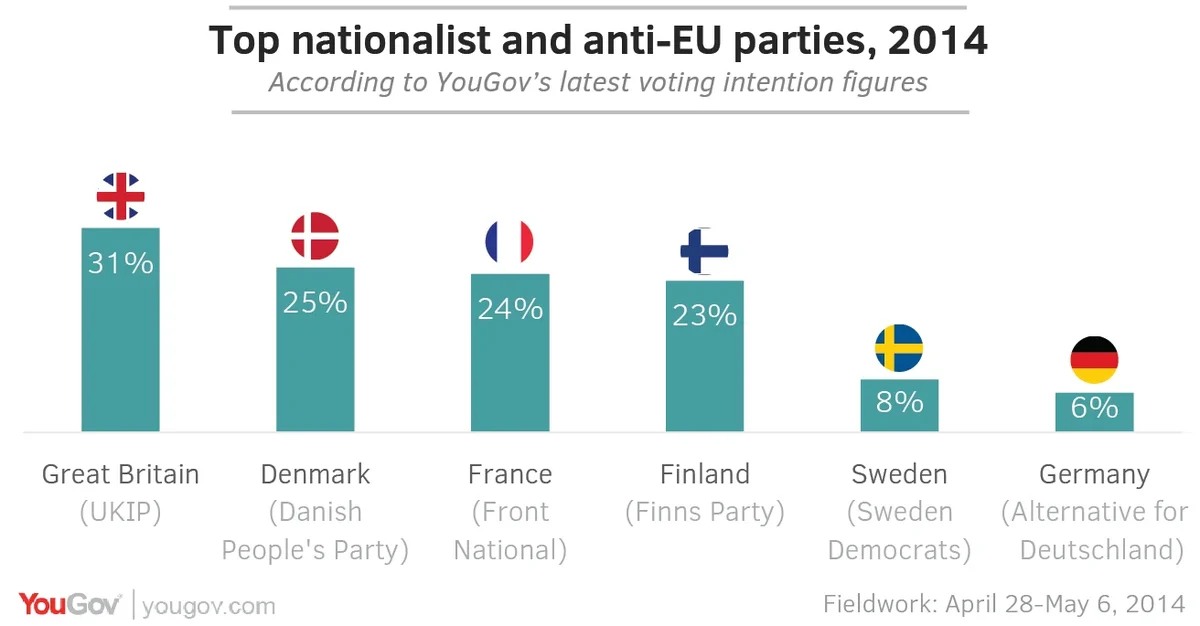

These figures indicate that in four out of the six countries surveyed – Great Britain, France, Denmark and Finland – a Euroskeptic or nationalist party is currently leading in voting intentions (in Finland there is a tie). In Germany and Sweden the anti-EU parties are both in fifth place.

In some countries, such as Denmark and France, there are additional Eurosceptic parties that would make the anti-EU share of the vote even larger.

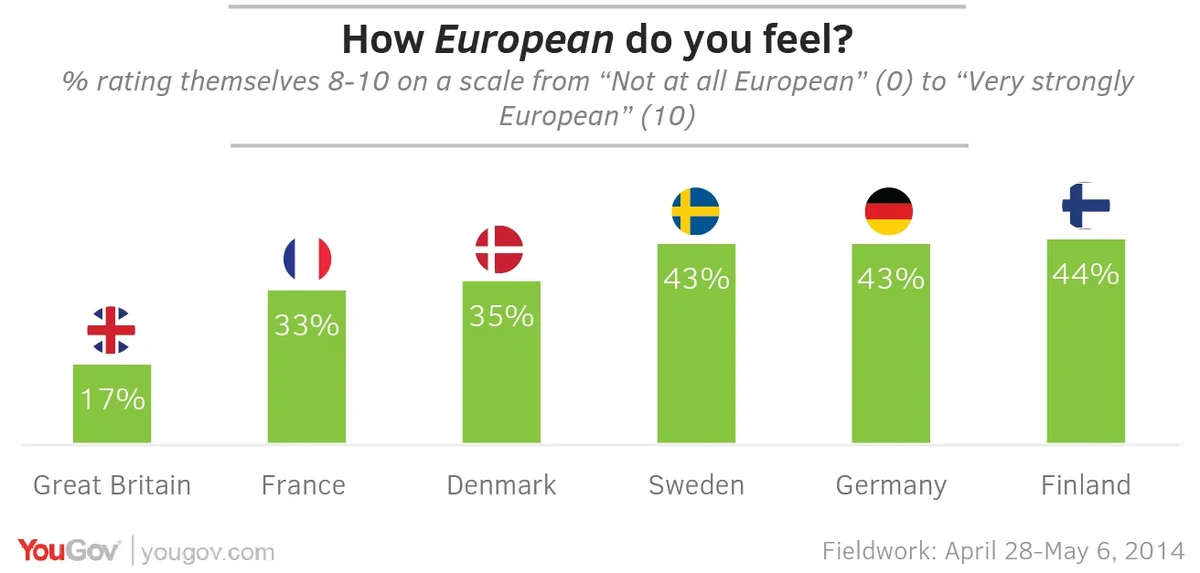

Interestingly, the popularity of these nationalist and Euroskeptic parties in Britain, Denmark and France, have a clear – albeit imperfect – inverse correlation with how strongly “European” people in each of those countries feel. Here, too, Britain stands out as the only country where less than a fifth of people rate themselves as very strongly European. France and Denmark, at 33% and 35% respectively, are next in line.

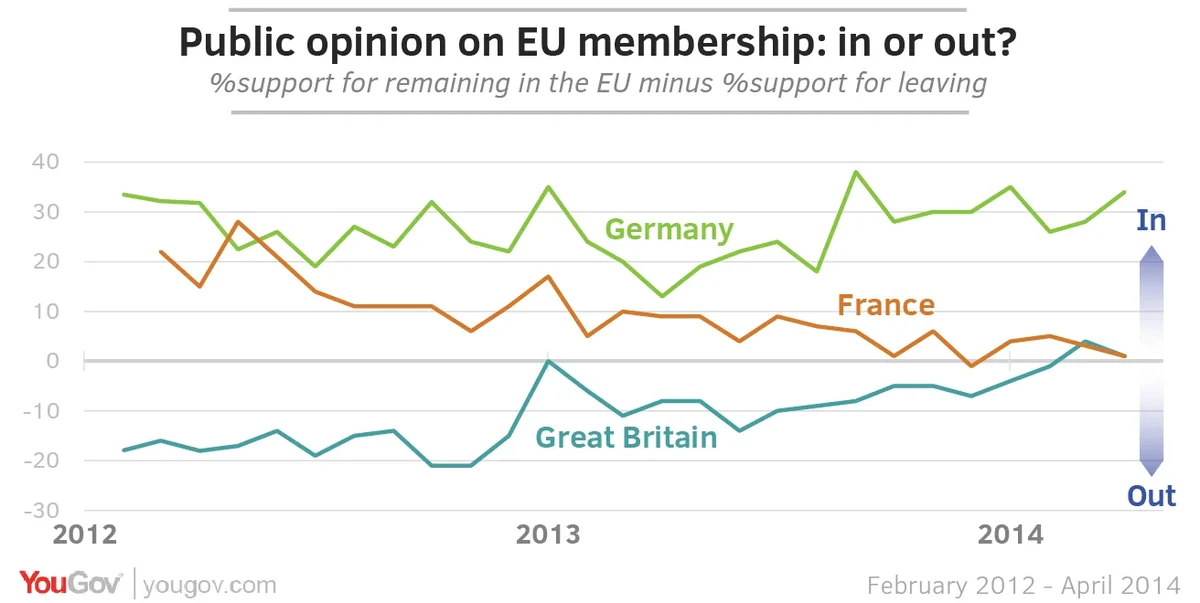

In Finland, however, where 23% intend to vote for the nationalist Finns Party, strong European identification is relatively common, at 44%. And it would probably be a mistake to interpret the rise of such parties as evidence of a surging anti-EU tide or even burgeoning nationalism. While increasing discontent with the European Union is certainly a factor, YouGov’s own polling and analysis have shown that plenty of UKIP’s own voters in the EP elections see their vote more as a vote against Britain’s other main parties than a vote against the European project. In the UK, there has in fact been rise in support for staying in the EU, which has come at the same time as UKIP’s recent resurgence:

In France, by contrast, Euroskepticism does appear to be on the rise. Previously, France was about as pro-EU as Germany which tends to support staying "in" by a substantial margin; today French public opinion on the European question has converged with British (33% in to 34% out vs 39% in to 38% out).

Of course, discontent with Europe is just one part of the puzzle: the European elections have become a venue for national electorates to protest against their national governments. As YouGov’s polling has previously shown, government approval and economic optimism in France have also cratered since 2012. In the latest polling, 56% of French voters agreed with the statement, “Most French politicians are personally corrupt”, the highest of the six EU countries surveyed (the number is 37% for the British public). In fact, government disapproval is above 50% in each EU country YouGov surveyed; though in Norway, which YouGov also surveyed, approval is roughly equal (37%) to disapproval (36%). Distrust in politicians is also high across the board (but again, lowest in Norway).

What also remains unclear in France, Britain and elsewhere, is whether the parties of the Euroskeptic Right will be able to carry over the momentum accumulated through local and European elections into the national parliamentary elections; and whether they will be able to co-operate with each other within the European parliament to form a powerful bloc.

See the full European voting intention results

See the full EuroTrack results

Image: Getty