According to several recent studies, good-looking candidates win more often and with higher margins (1,2,3). Like his father, Mitt Romney just looks like a president. How much is that helping him?

Answering that question is hard. To investigate it, I ran a simple experiment on a representative national sample. I asked participants to choose between pairs of Republican presidential candidates. Half the participants were randomly assigned to see pictures of the two candidates when choosing; the other half were not (the images that were shown are found below). If Romney’s appealing looks are giving him an advantage, we would expect him to fare better when participants saw his picture. In particular, we might expect the pictures to advantage him over Gingrich, as Gingrich seems the most disadvantaged in the looks department.

Of course, this with-and-without-picture test only works if people are somewhat unfamiliar with either Romney or Gingrich. If participants already know what they look like, seeing their pictures is unlikely to alter their choices. Fortunately for this experiment, ignorance persists. Although pundits often assume that Gingrich is a well-known commodity, they forget how little the public knows. In the same poll, I asked two factual questions about the candidates. Despite being one of the most prominent house members in history, only about 70% knew that that Gingrich had served in the US House of Representatives and only about 20% knew that Gingrich had previously supported an individual mandate for universal healthcare.

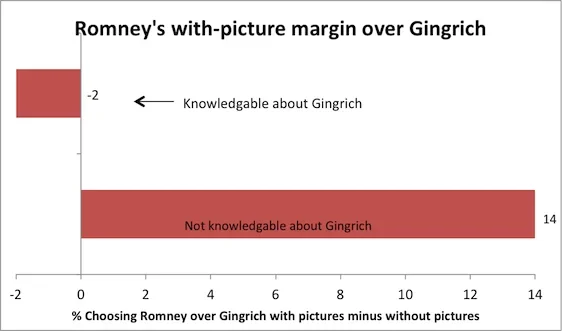

Participants who answered both questions incorrectly (251 of 998) are probably less likely to know what Gingrich looks like, and so pictures might hold greater sway over participants’ decisions. As the figure below shows, this is precisely what I found. The bars in the figure show the percent choosing Romney over Gingrich. On the left, the figure shows no real change in Romney's percent among those who appear somewhat knowledgeable about Gingrich: 67% chose Romney without pictures and 65% did so with pictures, a difference of -2.0 percentage points. (The lack of a difference does not necessarily indicate that appearance has no effect on informed voters — these respondents may have long since internalized the candidates’ appearances into their evaluations.) Among those who are somewhat ignorant about Gingrich, however, the pictures appear to have a substantial effect: 67% choose Romney without pictures and 81% do so with pictures, a 14-percentage point boost for Romney (p = 0.04).

We expect this effect to be even larger among those who are ignorant about Gingrich and Romney. Indeed, it is. Among individuals who incorrectly answered both questions wrong about Romney and Gingrich, the pictures gave Romney a 23-percentage point advantage. Most people, however, answered the questions about Romney correctly, so there are few such folks and so the results are suggestive at best (p = 0.18). I also included two other pairings, Santorum versus Romney and Perry versus Gingrich, and found similar but, as expected, less pronounced advantages (that is, I found advantages for Romney and Perry). As before, these effects are concentrated among the less knowledgeable respondents.

What does this all mean? These results provide suggestive evidence that Romney's appearance gives him an edge over Gingrich. Although people generally favor better-looking candidates in the studies noted above — where looks are measured by naïve raters — we can't say in any one case that it's appealing looks rather than something else in the pictures. Seeing Gingrich's face, for instance, could remind people of who Gingrich is, which could activate distant and not so flattering memories about him (think Clinton impeachment or the Air Force One incident).

Besides this concern about design, we also don't know whether looks matter in primaries. In a paper I wrote with Chappell Lawson, we found that candidate appearance primarily influenced poorly informed voters in general elections (for governor and senate). In primaries, these individuals may stay home — only the relatively informed may cast ballots. On the other hand, voters in states outside of the first few primaries may see little media coverage of the candidates and so lack opportunities to learn. Especially this year, they also have to choose between many candidates and so the informational demands are higher. To the extent they remain ignorant, Romney may be advantaged by his appearance, as this simple experiment implies.