In 1960, Richard Neustadt wrote Presidential Power, in which he told students of politics that presidential power was the “power to persuade.” Neustadt wasn’t so much talking about shifting public opinion, but Sam Kernell introduced that wrinkle in 1986. On May 9, President Obama announced that his opinion on gay marriage had changed – and ever since, analysts of public opinion have been looking for hints of presidential power. Can the president move public opinion? Did this president move opinion on this issue?

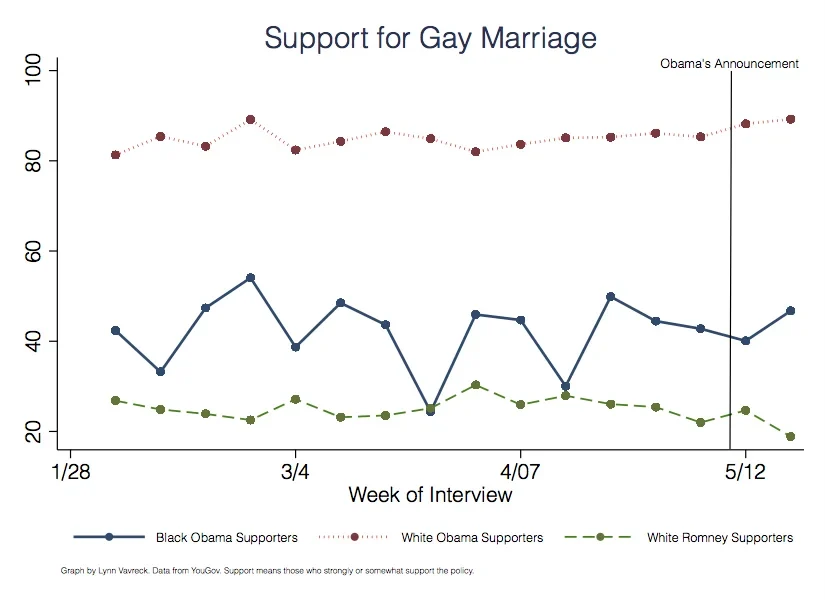

The wrinkle to exploit is that the president is black – and support for gay marriage among African Americans Democrats is much lower than it is among white democrats. In fact, black democrats look more like white Romney supporters than white Obama supporters, roughly (see graphic below). This unusual pattern presents an opportunity to witness a president leading opinion on a topic. Will support for gay marriage among black democrats increase now that the president has endorsed it?

Our answer to this question first appeared here. John Sides at The Monkey Cage summarized the ensuing debate here. And Ezra Klein similarly, here. All of us come down on the side of caution – if Obama is leading opinion-change on this topic, it is very hard to see it in the data. We have been asking a nationally representative sample of voters about support for gay marriage since February 4th of this year. Take a look at support (of any intensity) for gay marriage over time among three groups: black Obama supporters, white Obama supporters, and white Romney supporters.

These data are from weekly YouGov polls of a nationally representative sample of 1000 Americans, of which approximately 11% are black. We’ve plotted average levels of support for gay marriage over 16 weeks, which means we have roughly 16,000 observations of which 1,850 are black and 11,679 are white.

The first thing to notice in the figure is the increased level of variation among black Obama supporters relative to the other groups. This boils down to nothing more than an artifact of the size of that subsample (only 1,850 blacks compared to 11, 679 whites). There are more than six times as many whites in the sample as blacks, thus the estimates of black opinion will be measured with more imprecision relative to white opinion – this is just statistics.

The second obvious pattern in these data is the constant motion of each line – a little increase here, a little decrease there. Some of our political science colleagues call these kinds of patterns “bumps and wiggles.” Interpreting these bumps and wiggles, as any scholar of campaigns will tell you, is risky – especially post-hoc. The danger is two-fold: first, there is the undeniable urge to look for the movements and then find some cause that explains them. This is essentially identifying shifts in public opinion and looking for events that might have caused them, not terribly satisfying as science goes. A better approach would be to have a set of things that might drive movement (derived a priori) and then place those markers on the graph looking to see if they coincide with movement in opinion.

The second danger is in wanting to interpret the movement after a focal moment – like Obama’s announcement – as important, even if it resembles the average weekly fluctuations that came before it. Or worse, even it the movement after the important event is smaller than the average weekly fluctuations in the series (presumably most of which were not driven by similar moments!)

For example, the average weekly change in support for gay marriage among African Americans who support Obama is 10-points. That’s right – on average, opinions in support of gay marriage among black Obama supporters change 10-points week to week. The range of these changes goes from a whopping 21 and-a-half points between March 24th and March 31st to a low of -1 and-a-quarter points the next week (April 7th). There are also very large changes in support for gay marriage among this group for the weeks ending April 21 (19-points), March 24 (19-points in the negative direction), February 19th (14-points), and March 4th and April 14th (15 and 14-points respectively in the negative direction).

The week after Obama’s announcement, support for gay marriage among black Obama supporters went down by 2 and-a-half points. The following week if went up by 6 and-a-half points. These changes are small in comparison to the changes between each of the other pairs of weeks. They are in fact smaller than the average weekly change since February 4th. And importantly, we do not expect opinion on gay marriage to be fluctuating in this way week to week in response to political events. These changes are random noise; they reflect the uncertainty associated with each estimate of support.

Another way to see the danger in interpreting poll movements in isolation is to look at the changes from February 20th to the 26th. Support among black Obama supporters went up by 6.7-points, exactly the same amount of change the data show after Obama’s announcement from May 12th to the 19th. But on February 26th, support was jumping up to 54 percent – the highest in the series. On May 19th, it was ascending to 47 percent. If we want to interpret the post-Obama 6-point surge as meaningful, we better have a similar story for February 26th – and while we are at it, for all the other weeks (8 of the remaining 14!) between which the changes in support were greater than 6-points.

February 26th, it turns out, did end an important week of news about gay marriage: the Maryland legislature, on May 23rd, approved Gov. Martin O’Malley’s bill to legalize same-sex marriage. The vote in the Senate was close, and it got a substantial amount of coverage in newspapers across the country. So, if we engage in a little “bump and wiggle” analysis of these changes, we can report that Obama is leading black opinion on the topic about as much as the Maryland Governor and legislature – although the latter managed to actually push support for gay marriage among blacks up over the 50 percent mark, which Obama has yet to do.

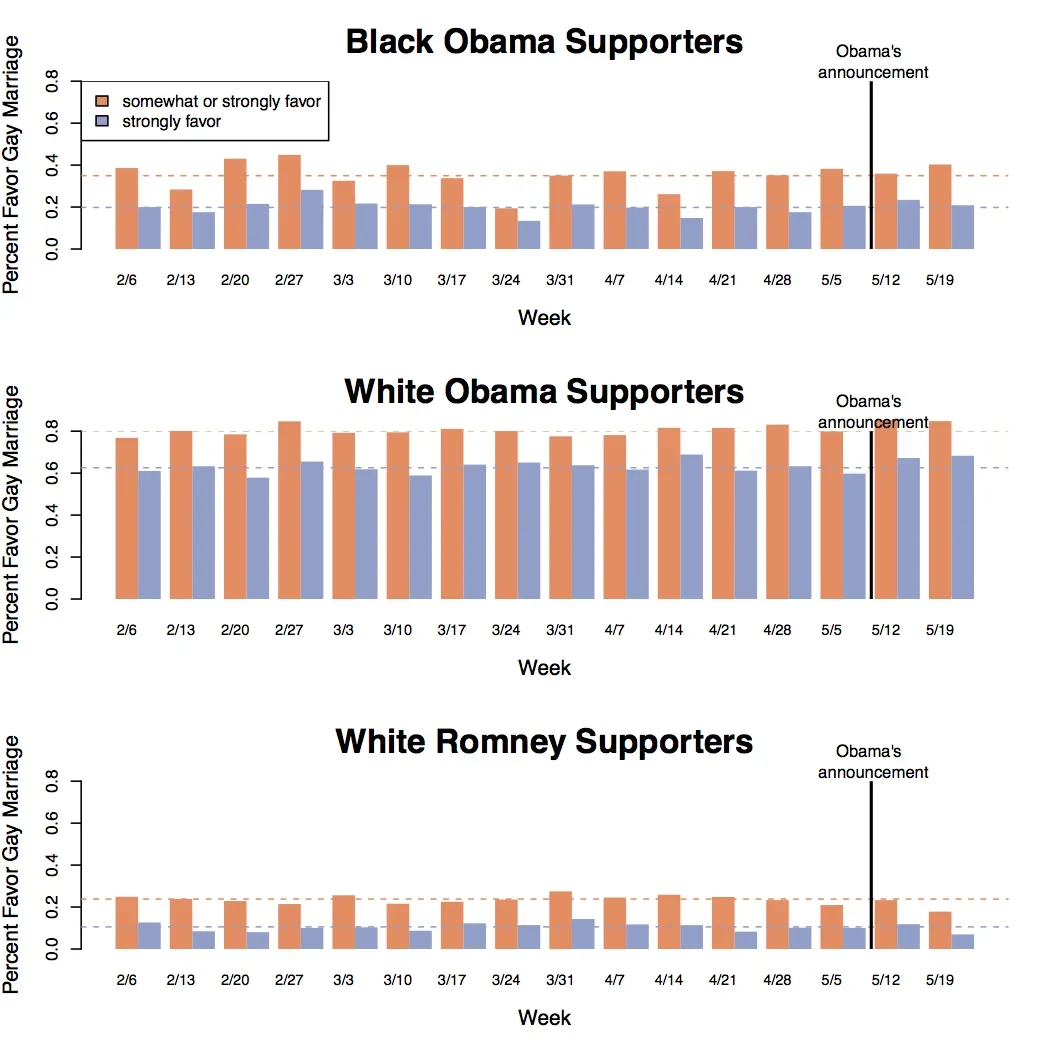

Separating out strong supporters from weak supporters of gay marriage does not change these patterns, as the figure below makes clear.

The dashed lines are the average support within each group before Obama’s announcement. Orange bars include supporters of any intensity and purple bars are only people who “strongly” support the policy.

The same kinds of patterns can be seen among white voters as well – both those voting for Obama and Romney. Among white Obama voters’ support for gay marriage is at it highest on May 19th after the announcement, but another week in which it hit this zenith is February 26th – after the Maryland law was passed. But mainly, among white voters you can see the ebb and flow of the noise in these polls. Support goes up and then it goes back down, over and over – mean reversion. The magnitude of the swings are not as big as they are among blacks because of the increased sample size for white voters relative to black voters, but the warning is the same: beware of interpreting the bumps and wiggles.