The intense focus of journalists and pundits on the disappointing monthly job report — only 69,000 jobs were created — points to one of the great mysteries of presidential voting: why voters care so much about the election-year economy. According to numerous studies, voters mostly ignore economic booms or busts in the first three years of terms and judge the president and his party on the election-year economy. In fact, they are primarily influenced by growth only in the six months before Election Day. Voters appear not to be answering Reagan's question, "are you better off than you were four years ago?" Instead, they are answering the question, "are you better off than you were six months ago?"

Why are voters seemingly so shortsighted? In a working paper, Andy Healy and I propose and test an explanation based on recent research in psychology. Since the early 1990s, psychologists have reported a surprising finding. When retrospectively assessing experiences, people often rely on the end. In one of the better-known examples, patients evaluated their pain during a colonoscopy, not on the overall experience, but on the pain experienced at the peak and the end. Daniel Kahneman, who conducted this study, calls the mechanism behind this tendency attribute substitution. When people attempt to make even slightly difficult judgments, such as evaluating the overall experience of a colonoscopy, they often inadvertently substitute a related attribute that is more readily available, such as pain at the end.

Andrew Healy and I find the same tendency appears to explain voters’ preoccupation with the election-year economy. Voters’ perceptions of the economy during a president's term, we find, are unduly influenced by the end. Voters want to judge the president on the entire term, not just the election year, but evaluating the term economy isn't easy for voters. Government agencies and the media rarely report on, say, cumulative income growth during the term, and voters don't keep track themselves. When voters try to evaluate the term, they substitute the end for the whole without realizing it.

Are voters making the same substitution in 2012? Are their perceptions of the economy under Obama overly influenced by their perceptions of the current economy?

To provide a simple test, I asked respondents a series of questions about the economy on a YouGov poll. I first asked about the condition of the national economy during Obama's term. I then asked about the national economy in 2009, 2010, 2011, and "these days." For each period, the question simply asked, "how would you rate the national economy [period]." For the question about Obama's term, I used "since 2008." Respondents could answer on a four-point scale: very good, fairly good, fairly bad, and very bad.

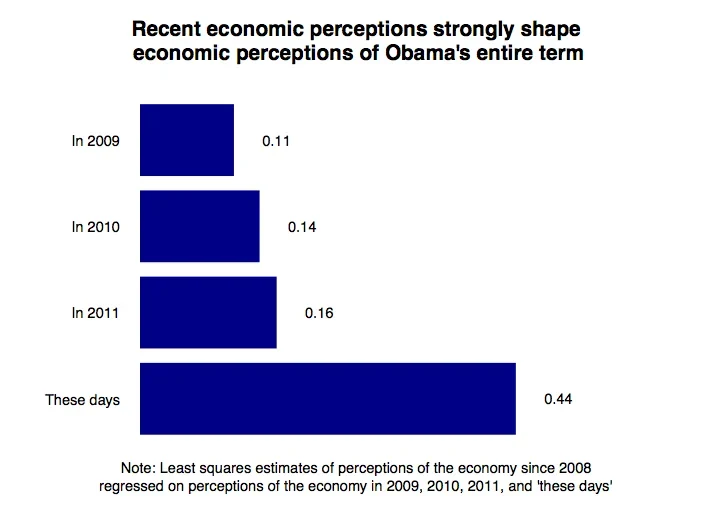

If respondents accidentally substitute the present economy for the past, their perceptions of the economy "these days" should better predict perceptions of the economy since 2008 than should perceptions of other years. To test this prediction, I estimate a (least squares) regression model where the outcome variable is perceptions of the economy since 2008 and the explanatory variables are the four period-specific questions about the economy. This statistical approach attempts to hold constant the effect of each period—showing the effect of, for instance, the economy "these days" while controlling for the effect of the other years on people's memories.

As the figure below makes clear, however, respondents’ memories of the economy under Obama appear unduly influenced by their perceptions of the recent economy. Each bar shows the effect of a one-point increase in its respective period—say from "very bad" to "fairly bad" in 2009—on perceptions of the economy since 2008. Perceptions of first three years of Obama's term, the figure shows, have quite small effects on overall evaluations. For example, a one-point increase in perceptions of the economy in 2011 led to a small 0.15 increase in perceptions of the economy since 2008 (remember that the questions are on a four-point scale). In contrast, a one-point increase "these days" led to almost a 0.44-point increase, almost half a point. Put differently, the recent past appears to count for three times more than earlier years of Obama's presidency.

This intriguing finding may in part explain the election-year economy’s strong influence on voters, but it is of course open to alternative explanations. For example, respondents may have interpreted "these days" liberally to include much of Obama's term. The finding is also observational, so reverse causation or some other variable could lie behind it, though the finding holds up when controlling for approval of Obama and party identification. Andrew Healy and I have also replicated similar findings in other years and with panel surveys, and this finding is consistent with the experimental results we present in the working paper I linked to above.

Can this tendency be cured? We think so. In the experiments we have conducted, simply providing voters with economic information about the entire term, such as cumulative income growth, rids voters of the year election-year focus. They don't want focus on the election year, and don't when they can easily make judgments about the term.