Mitt Romney’s choice of Paul Ryan as his running mate puts fiscal policy—government spending, taxes, and debt—squarely in the center of this year’s presidential campaign. The latest YouGov survey suggests that expectations about future budget deficits under President Obama or President Romney were having a major impact on prospective voters’ choices even before Ryan joined the Republican ticket—and advantaging Romney. But those expectations seem to reflect a good deal of confusion, misconnection, and wishful thinking.

Ryan has spent much of his career warning America of “a crushing burden of debt” that “will soon eclipse our economy and grow to catastrophic levels in the years ahead.” Whichever candidate wins in November will have to wrestle with the long- term federal budget deficit, a “debt bomb” that budget analysts attribute primarily to the escalating cost of health care and the aging of the Baby Boom generation. Paradoxically, he will also face a looming “fiscal cliff” on January 1st, when the expiration of the Bush tax cuts and the Obama payroll tax cut and the imposition of automatic spending cuts mandated by the 2011 debt ceiling deal threaten to wreck economic havoc by abruptly reducing the rate of deficit spending.

YouGov asked 1000 prospective voters “how the outcome of this fall’s presidential election will affect America over the next four years. Regardless of which candidate you personally support, what effect do you think the election outcome will have on the federal budget deficit?” The response options were “much higher if Obama is reelected” (selected by 35% of the sample), “somewhat higher if Obama is reelected” (11%), “no difference” (36%), “somewhat higher if Romney is elected” (5%), and “much higher if Romney is elected” (12%).

The distribution of responses to this question is a testament to the political effectiveness of Republicans like Ryan and Tea Party activists, who have been loudly bewailing the escalation of the federal debt since Barack Obama became president. Democrats’ counterargument that recent outsized budget deficits reflect fallout from the 2008 Wall Street meltdown, the Bush tax cuts, and the Iraq War seems to have been much less persuasive. Nor have they made much headway, at least so far, in convincing the public that the Republican budget plan authored by Ryan and endorsed by Romney would actually exacerbate the deficit by slashing the taxes of top income earners.

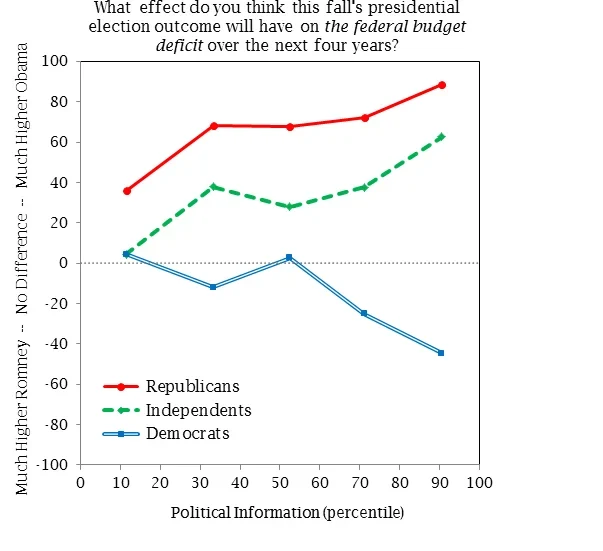

Despite the question wording encouraging respondents to put aside their own candidate preferences, expectations regarding future budget deficits are strongly skewed by partisan predispositions (as measured in a “baseline” survey of the same respondents in late 2011). Most Democrats think deficits will be larger if Romney is elected, while most Republicans (and independents) expect bigger deficits under Obama. As is often the case with politically charged beliefs, this partisan gap is especially large among people who are especially knowledgeable about politics.

While expectations about future budget deficits are partly just a reflection of partisan predispositions, they do appear to be having a substantial independent influence on prospective voters’ thinking about which candidate to support. For example, among “pure” independents, those who expected the deficit to be “somewhat higher if Obama is reelected” were 28 points more likely to say they would vote for Romney than those who expected the deficit to be “somewhat higher if Romney is elected”—even after statistically controlling for perceptions of the national economy and whether the country is on the right or wrong track, expectations regarding overall economic growth under President Obama or President Romney, personally liking or disliking each candidate, political ideology, and views about gay marriage.

Mathematically, the federal budget deficit is simply the gap between federal spending and tax revenues. Thus, if either candidate would preside over more spending and less taxing, there is no logical way to escape the implication that the budget deficit would be higher than under his opponent. While the YouGov survey did not confront respondents with this fiscal logic in pure form, it did include a series of questions about how they thought the election outcome would affect (1) “federal spending on Medicare and Social Security,” (2) “federal spending on domestic programs like education, food stamps, and highways,” (3) “defense spending,” and (4) “your own federal taxes.”

Of the 1000 respondents in the survey, 93 provided answers to these questions indicating that spending would be higher and that their own taxes would be lower if Barack Obama is reelected; but only 15% of those people drew the conclusion that the federal budget deficit would be higher under Obama, while 55% said it would be higher under Romney. Conversely, 49 respondents indicated that spending would be higher and that their own taxes would be lower if Romney won in November; but only 3% of them inferred that the deficit would be higher under Romney, while 94% said it would be higher under Obama!

Of course, it is possible to explain away these apparent contradictions by supposing that respondents expect other people’s taxes to be affected much differently than their own by the election outcome. For example, middle-class and poor people who expect higher spending and lower taxes under Obama may suppose that wealthy people’s taxes will go up enough to erase the resulting budget deficit. However, as a practical matter that seems quite unlikely to happen—and in any case, there is rather little evidence in the survey that respondents’ own economic circumstances had much effect on their expectations about future taxes. The most plausible explanation of these beliefs is simply that people are strongly inclined to think that the candidate they prefer is more likely than his opponent to deliver all good things, including government services, low taxes, rainbows, ponies, and a balanced budget.

Is the magical fiscal thinking displayed by these 142 people—14% of the YouGov sample—atypical? Not really. In order to examine the broader public’s thinking about budget deficits, I analyzed the statistical connection between all respondents’ expectations about the budget deficit on one hand and their expectations about government spending, taxes, and economic growth on the other hand. (All of these expectations were elicited as part of the same battery of questions about “how the outcome of this fall’s presidential election will affect America over the next four years.” All are similarly coded to range from −1 to +1, with 0 representing “no difference” between Obama and Romney.)

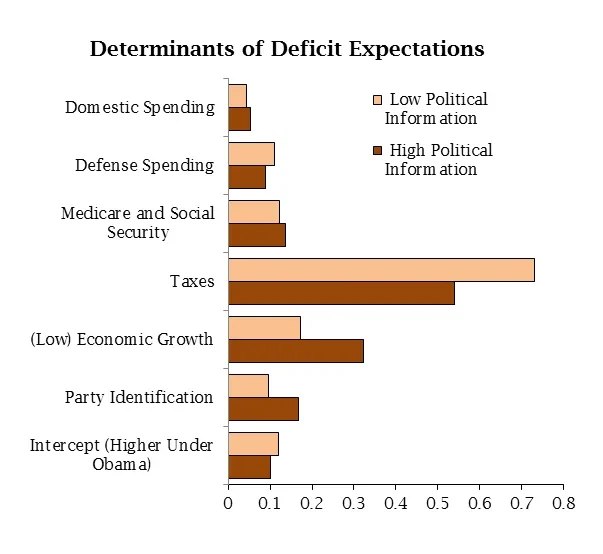

The accompanying figure shows parameter estimates from separate regression analyses of deficit expectations for survey respondents with below-average levels of political information and those with above-average levels of political information. (The standard errors of these parameter estimates range from .02 to .04; thus, all of the estimates except those for domestic spending are “statistically significant” by conventional standards.)

The three questions tapping expectations about federal spending were all positively related to expectations about the deficit; but the relationship was modest for expected spending on defense and entitlement programs and even more modest for expected spending on domestic programs. Wherever budget deficits come from, in the public mind, they do not seem to come primarily from higher levels of government spending.

The strongest relationship, by far, was between people’s expectations about the budget deficit and their expectations about their own taxes. However, the direction of this relationship was precisely the opposite of what straightforward fiscal logic would suggest: people who expected higher taxes under Obama also expected a bigger budget deficit under Obama, other things being equal, while those who expected higher taxes under Romney also expected a bigger budget deficit under Romney. This peculiar association was strongest among people who were relatively uninformed about politics; but it was easily the most important single determinant of deficit expectations even among people with above-average levels of political information.

Expectations about the federal deficit were somewhat less strongly related to expectations about overall economic growth. People who thought the economy would grow more robustly under Obama thought the deficit would be larger under Romney, and vice versa. (Not surprisingly, expectations about relative economic growth were themselves strongly skewed by partisan loyalties; 47% of Democrats and 66% of Republicans expected higher growth under their party’s candidate, while only 11% of each group expected higher growth under the other party’s candidate.) People’s partisan attachments also had a substantial direct effect on their expectations about the deficit, even after taking statistical account of all these other factors.

The intercept in the regression analysis points to one final anomaly in the public’s deficit expectations. Given the way the explanatory variables in the analysis are measured, the intercept represents the expected response to the deficit question among people who provided neutral responses to all of the other questions—“pure” independents who expected economic growth, domestic spending, defense spending, entitlement spending, and their own taxes to be the same regardless of who wins in November. It is hard to see why people with this configuration of views would expect a bigger budget deficit under President Obama than under President Romney (or vice versa). Nevertheless, they did—and this difference alone depressed Obama’s expected vote by about two percentage points.

Why would prospective voters expect a bigger budget deficit under Obama than under Romney, even with identical levels of economic growth, government spending, and taxes? Perhaps they think the stork will bring it.