With so much of this year’s campaign focusing on taxes and tax policy, it might seem unlikely that prospective voters could still be swayed by learning a basic fact about the U.S. tax system. However, last week’s YouGov survey found that 44% don’t know it—and that they are 6 points less likely to vote for Mitt Romney as a result. What is this magic fact? That almost half of Americans pay no federal income tax.

When a video surfaced of Mitt Romney telling donors that 47% of Americans pay no federal income tax, pundits were quick to declare it “an utter disaster” that “killed Mitt Romney’s campaign for president.” After first saying that his points were “not elegantly stated,” Romney later called them “just completely wrong.”

Much of the commentary on the “47%” flap challenged Romney’s characterization of people who don’t pay federal income tax as “dependent on government” and unwilling to “take personal responsibility and care for their lives.” But almost all of it noted that Romney’s basic premise was essentially correct—according to the latest figures from the Tax Policy Center, 46% of American households paid no federal income tax in 2011.

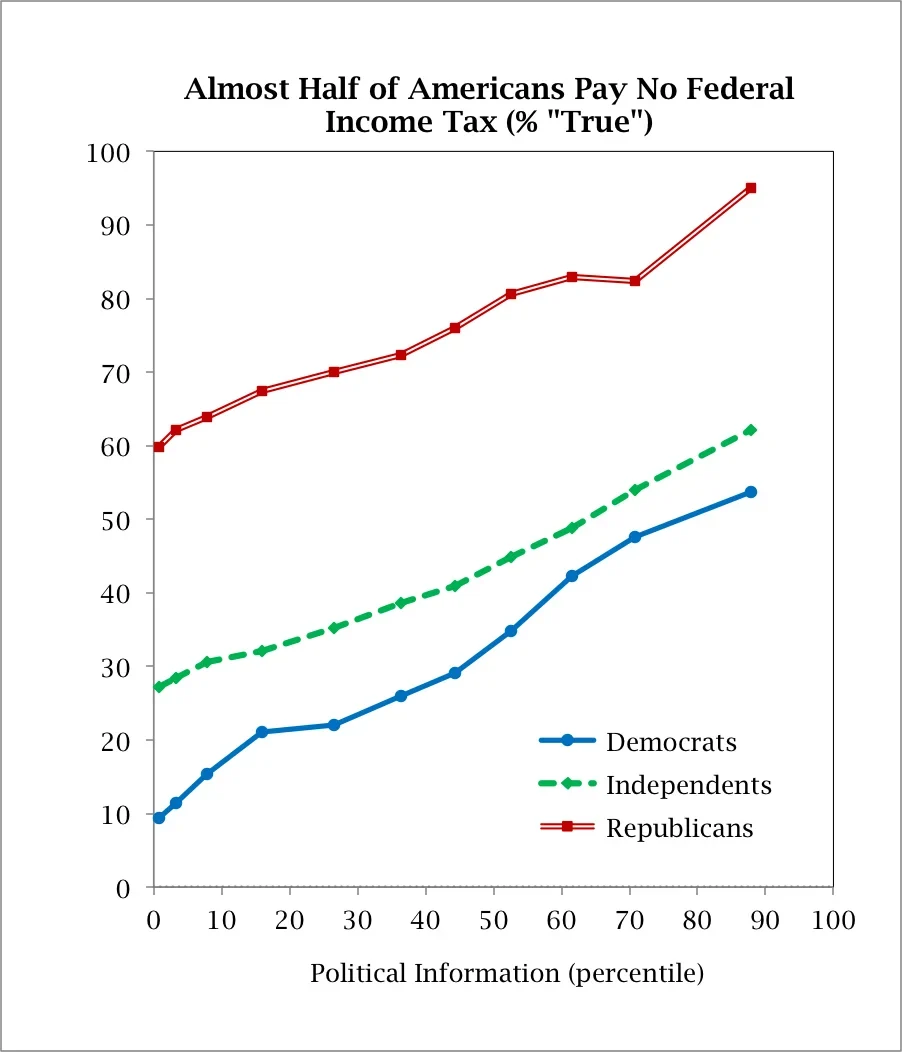

With all this attention to “the 47%,” one might suppose that everyone now knows this simple fact about the U.S. tax system; but that supposition would be wildly off-base. The YouGov survey reminded 1000 people that “Mitt Romney has claimed that almost half of Americans pay no federal income tax,” than asked, “Do you think that claim is true or false?” Only 55% said true, while 44% said false. Nor were the skeptics simply committed Democrats toeing the party line; people who are generally less knowledgeable about politics were much less likely to accept Romney’s claim regardless of their own partisan views.

Would it matter if these people knew how many Americans don’t pay federal income tax? Comparing the vote intentions of otherwise similar respondents (controlling statistically for party identification and assessments of President Obama’s job performance, Romney’s likeability, and national economic conditions), those who accepted Romney’s claim were 6 points more likely to say they would vote for him than those who didn’t. Was this just a matter of trusting Romney? Apparently not, since they were also 9 points more likely to say they would vote for a Republican House candidate. These estimates suggest that Republicans could gain significant support by convincing even half of those doubters that Romney’s controversial remarks about a dependent class were grounded in a true fact about the U.S. tax system.

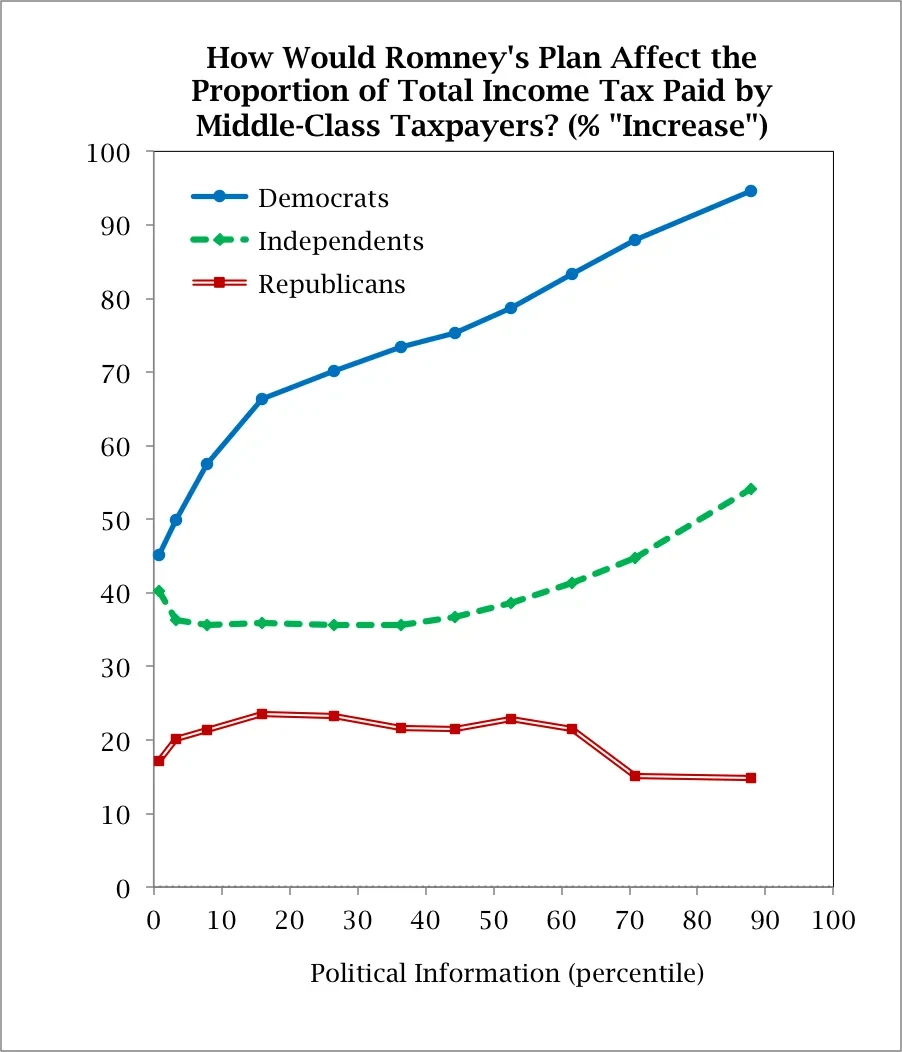

Another item in the YouGov survey reminded people that “Mitt Romney has proposed a major reduction in tax rates financed by the elimination of various tax deductions,” then asked, “Do you think Romney’s plan would increase or decrease the proportion of total income tax paid by middle-class taxpayers?” 46% of the respondents said the middle class would pay a larger share, while 53% said its share of the total tax bill would remain unchanged (35%) or even decrease (18%).

As with beliefs about how many people don’t pay taxes, these expectations about the impact of the Romney tax plan seem to have a significant impact on vote intentions. Other things being equal, someone who expected the middle-class tax share to increase was 4 points less likely to support Romney—and 6 points less likely to support a Republican House candidate—than someone who expected the middle-class tax share to decrease or remain unchanged.

A variety of independent analysts have argued that Romney would be unable to reduce tax rates significantly without either escalating the federal deficit or increasing the tax share of the middle-class; there simply are not enough deductions going to high income-earners to offset a major reduction in their tax rate. In the first presidential debate, Barack Obama struggled to explain this apparent inconsistency in Romney’s proposal, but he was stymied by the complexity of the issue and by Romney’s flat insistence (with a nod to “six other studies”) that his plan “will not add to the deficit” and “will not under any circumstances raise taxes on middle-income families.”

Not surprisingly, in light of this complexity and contentiousness, the pattern of beliefs about the impact of Romney’s tax plan looks quite different from the corresponding pattern regarding how many people don’t pay federal income tax. While better-informed Democrats were significantly more likely to say that Romney’s plan would increase the share of taxes paid by the middle class, the impact of political information among Independents was much more muted—and the best-informed Republicans were slightly less likely to agree.

With “all these studies out there” (as Romney put it in the debate), attention to politics mostly seems to have widened the partisan gap in assessments of how Romney’s tax plan would turn out to affect middle-class taxpayers. That is a big challenge for Obama and others who want to convince uncommitted voters that Romney’s plan is a Trojan horse for reducing taxes on the wealthy. Obama said in Denver, with some exasperation, “it’s math.” But math is hard, especially when it’s about the future. By comparison, convincing uncommitted voters that the existing tax system exempts a lot of people from paying income taxes seems a lot less daunting. If Republicans can spread that word—without getting caught up in the ugly stereotyping that sidetracked Romney last month—the information campaign could have a significant political pay-off in November.