As argued in a classic article, the role of campaigns in democracy is to inform voters about the candidates, especially about their policy stances. In a book I recently published, Follow the Leader (press release), I find considerable evidence that campaigns fulfill this role: voters often do learn about candidates’ and parties' positions during campaigns. Surprisingly, however, I find that voters generally fail to act on their newly acquired information. For example, only about half of the electorate typically knows that the Democratic Party is more liberal than the Republican Party (after corrections for guessing). During presidential election campaigns, however, many individuals learn this most basic political fact. When I analyzed these campaign “learners,” however, I found no evidence that this learning changed their views about candidates or parties. When conservatives learned which candidate was more conservative, for instance, they did not become more likely to vote for or more approving of the conservative candidate.

One explanation for this strange finding, which I have replicated for many policy issues and for other elections, is that the kinds of people who learn about the candidates' or parties' positions during campaigns are also the kinds of people who just don't care about policy issues. A corollary of this explanation is that such learning would matter when voters who care about policy have something new to learn during the campaign. The 2012 campaign appears to be one of those cases. In contrast with most elections, where candidates’ and parties’ stances remain mostly unchanged, the 2012 election is unusual in that voters have something new to learn about: Mitt Romney's policy stances.

According to popular accounts, candidates often move towards the extremes during primary campaigns, but few have tacked as far as the former governor of Massachusetts, one of the most Democratic states in the nation. As Romney turned his eye to the presidency in the mid-2000s, he became more conservative. Journalists and pundits noted the shift at the time, but much of the electorate apparently did not. As John Sides recently showed with an elegant graphic, that's finally changing: the public's perception of Romney has been slowly shifting conservative—catching up with his actual stances—though the public still sees Romney as more moderate than it sees Barack Obama. In January of this year, for instance, about 30% of the public placed Romney as a “3” on YouGov’s five-point ideology scale, where 1 is most liberal and 5 is most conservative. Now, only about 18% place him as a 3, a considerable drop.

Has Romney's rightward shift hurt him in the general election? Since many voters are only now learning about Romney's shift, the YouGov survey allows us to attempt to answer this question. YouGov interviewed respondents in January and has been reinterviewing them ever since. In each interview, the survey asked respondents to place themselves, Obama, and Romney on the same five-point ideology scale. We can therefore use this scale to determine who learned since January about Romney's conservative shift. To do so, I examined how respondents' perceptions of Romney's ideology changed relative to their perceptions of Obama's ideology (which helps eliminate individual differences in the use of the ideology scale). Specifically, I looked at respondents who learned that Romney is more conservative than Obama. I coded people as learning about Romney's shift if they failed to place him as more conservative than Obama in January, but did so in their recent interview. (Other approaches produced similar results.) According to this measure, about 14% of the respondents learned about Romney’s shift.

(What happened to the rest? Only 58% saw Romney as more conservative in both interviews, 22% either failed to place Romney or Obama on the ideological scale, placed them both at the same position, or placed Romney as more liberal than Obama. Almost 5% appeared to “forget” that Romney was more conservative, and failed to place him or placed him as more liberal during the reinterview.)

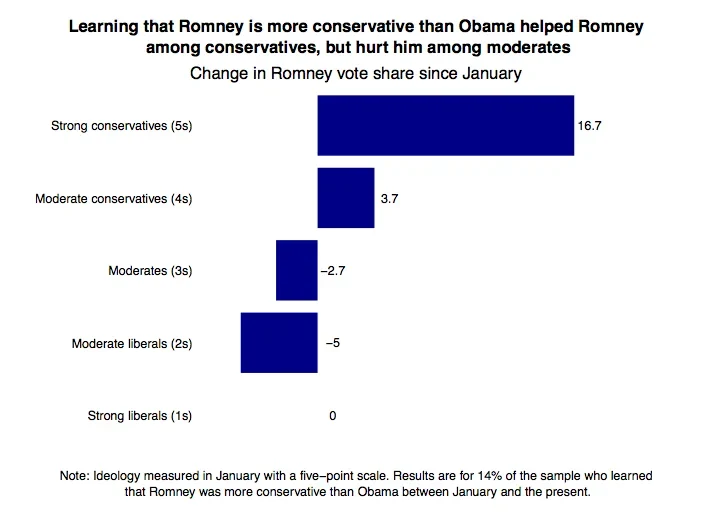

Has Romney's conservative shift hurt or helped him among the 14% of the electorate who learned since January that he is more conservative than Obama? The YouGov survey provides strong evidence that it helped him among conservatives. The most conservative respondents (5s on the ideology scale as measured in January) did increase their support for Romney by 16.7 percentage points, from 65% saying they would vote for him to 82 % saying so, a sizable increase. Moderately conservative respondents (4s on the five-point scale), also shifted towards him, but by only 3.7 percentage points.

What about moderates and liberals? The shift hurt Romney but not by that much. Moderates (3s on the five-point scale) shifted against him by 2.7 percentage points, moderate liberals (2s) shifted against him by five percentage points, and finally the strongest liberals (1s) were already overwhelmingly voting against Romney and did not shift further.

What's the net effect on Romney support? Even though strong conservatives have become much more supportive of Romney, they constitute a tiny fraction of the electorate. Most voters are moderate. In the YouGov survey, for instance, only 11% placed themselves at 5 on the ideology scale. In contrast, 36% placed themselves at 3. So, across all learners, Romney’s shift turns out to have hurt him by about one percentage point—not much, but everything counts in an election as close as this one.

According to these findings, the 2012 campaign has fulfilled one of its main roles in democracy: it has informed voters about Romney's new policy stance. Moreover, in contrast with my findings in other elections, voters have shifted their vote intentions accordingly, probably because voters who care about ideology had something new to learn.