John Sides has done an excellent job throughout this campaign season documenting how Americans are often unaware of the ostensibly game-changing moments that the media deem so important. For his latest installment, Sides reveals that less than half of the respondents in a recent YouGov poll knew President Obama said the private sector was doing fine earlier this month–a gaffe that received tremendous media attention.

Along with inattention, a second obstacle to gaffes impacting election outcomes that can be deduced from John Zaller’s groundbreaking theory of opinion change is that American’s who know about political missteps should have more crystallized political preferences than those who don’t. That is, gaffe-receivers are expected to be less persuadable.

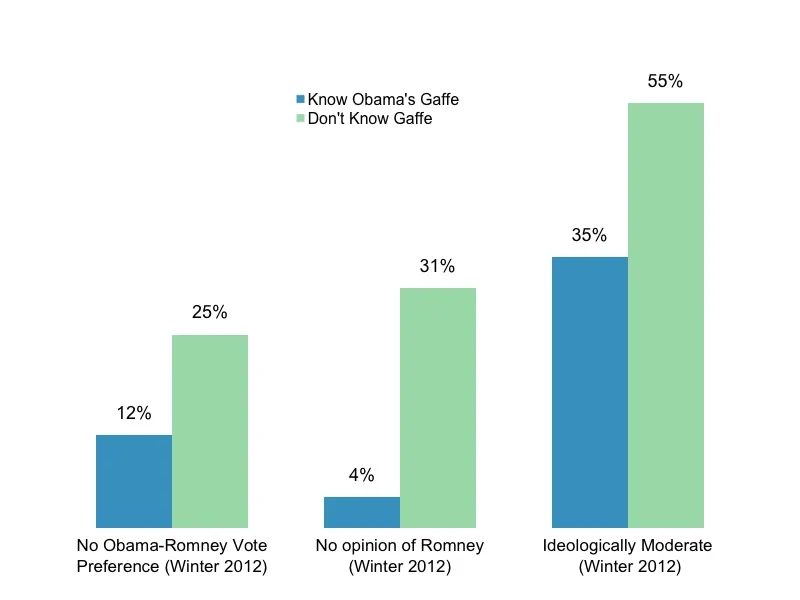

Fortunately, some unique survey data collected by YouGov last week allows us to test that expectation. The poll re-contacted a nationally representative sample of 1,000 individuals who were previously interviewed in this past winter. We can leverage the re-interview component of that survey to determine whether respondents who knew Obama said the private sector is doing fine had more solidified political opinions going into the election year than their less informed counterparts. Consistent with that expectation, the results below show that gaffe-receivers were much more likely to have a preference in early-year match-ups between Obama and Romney. A far greater proportion of these individuals were also able to rate Romney on a favorability scale in that original survey, and identified as liberals or conservative, than their less attentive counterparts.

(Source: YouGov Panelists from Winter 2011-2012 who were re-interviewed Jun 16-18, 2012)

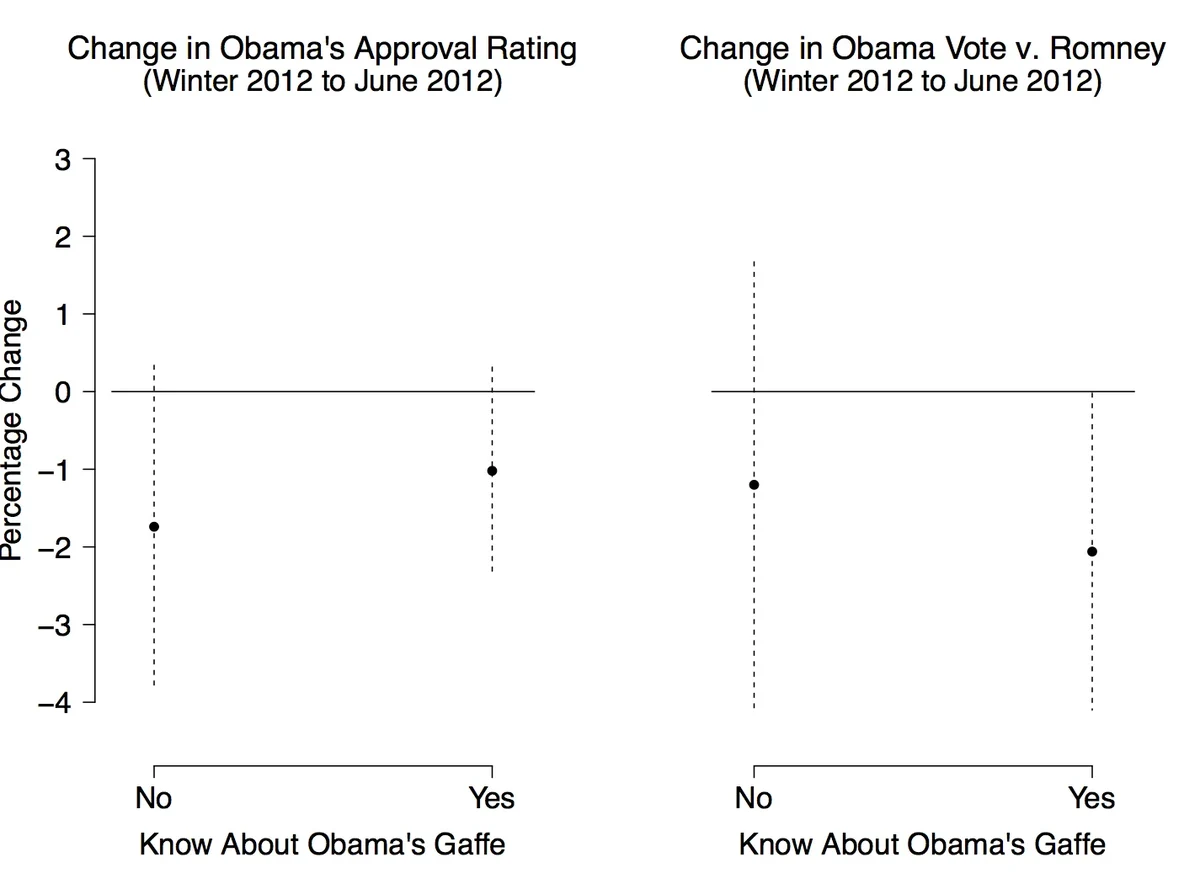

It is not too surprising, then, that gaffe-receivers were no more likely to change their opinions about Obama over the course of the campaign than respondents who did not know Obama said the private sector was doing fine. The figure below, for instance, shows that there was hardly any difference in either vote change or Obama approval change from early in the election to June 2012 between those who could and could not identify Obama’s gaffe–a result effect that holds when controlling for political attitudes that could also be correlated with gaffe reception.

(Source: YouGov Panelists from Winter 2011-2012 who were re-interviewed Jun 16-18, 2012. Note: Dashed lines are 95 percent confidence intervals)

To be sure, this quick analysis cannot rule out the possibility that gaffes could have some influence among those paying attention. However, it does suggest that any potential effect is quite small at best. And given that even large political communication effects decay rapidly as different considerations are made salient by new information (see here and here), there is no reason to believe that a political gaffe in June will have any bearing on November voting.