Back in January, Lynn Vavreck, Joshua Tucker, and I asked this question: what would happen if people knew more specific details about Mitt Romney's income and tax rate? We conducted a simple experiment that exposed people to information about these topics. In this post, I will report on a new iteration of this experiment, which seems particularly timely in light of this Obama ad, for example.

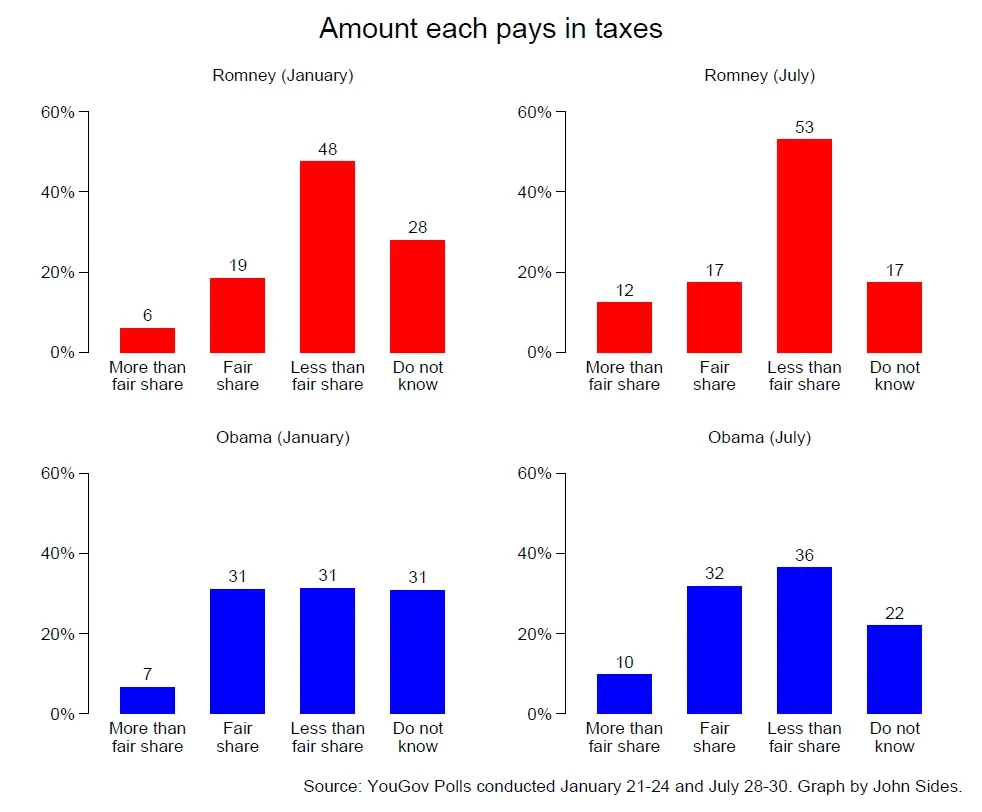

In our first study, we found that Americans tended to think that Romney did not pay his "fair share" of taxes. In a July 28-30 YouGov poll, the same was true, and perhaps even more so. Compare perceptions of Romney and Obama in January vs. July:

During these six months, the percentage who had no opinion about what Obama and Romney paid has declined. For both candidates, the percentage saying that they paid less than their fair share has increased (by about 5 points). Romney's disadvantage on this issue remains: a slight majority of Americans now believe that he does not pay his fair share. And this is not something that only Democrats believe. Almost half (48%) of "pure" independents believe this as well.

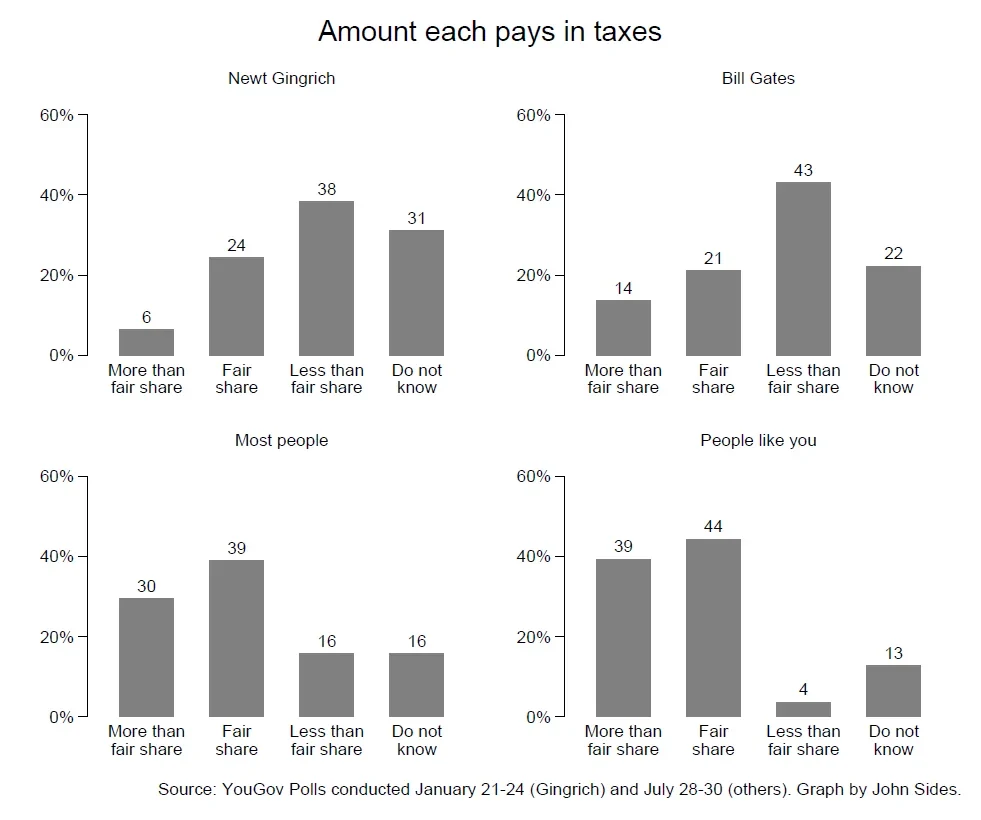

For comparison, here is how respondents felt about the taxes paid by Newt Gingrich, Bill Gates, "most people," and "people like yourself." This shows, for example, that perceptions of Romney are less favorable than those of Gingrich and Gates.

After July respondents had answered these questions, a half-sample was assigned at random to see one of the following:

- Information about how the average American’s income compares to Romney’s: “The Census Bureau has estimated that the average American household earned about $50,000 in 2010. In August, Mitt Romney disclosed that in 2010 he and his wife had earned somewhere between $7 million and $40 million.”

- Information about how federal tax rates for different income levels compare to Romney’s: “In this country, a person making under $20,000 each year pays about 2% of their income in federal taxes. A person making $60,000 pays about 13% of their income in federal taxes. A person making $250,000 pays about 20% of their income in federal taxes. Last week, Mitt Romney suggested that he paid about 15% of his income in federal taxes.”

- Information about average income and tax rates, with no mention of Romney: ““The Census Bureau has estimated that the average American household earned about $50,000 in 2010. In this country, a person making under $20,000 each year pays about 2% of their income in federal taxes. A person making $60,000 pays about 13% of their income in federal taxes. A person making $250,000 pays about 20% of their income in federal taxes.”

This experiment was designed before Romney had released some details about his income and tax rate, but the information in the experiment corresponds closely to what he released, as we noted in the original post. For the sake of strict continuity, I opted to keep the experiment the same rather than change it to reflect what Romney released.

Below I compare the key findings from the January experiment -- quoting from the earlier post -- with new analysis from the July experiment:

...respondents who saw information about either Romney’s wealth or tax rate were less likely to believe he “cares about people like me”—provided they already believed he wasn’t paying his fair share of taxes.

In other words, a group that didn't like Romney very much to begin with liked him a little less after seeing this information. In the July experiment, however, even this modest finding did not emerge. Neither piece of information affected perceptions of Romney on this dimension.

...being told Romney’s income increased the percentage who said that “cares about the wealthy” describes Romney “very well”...

The same is true in July. In general, Americans now perceive Romney as more concerned about the wealthy than they did in July. In July, 50% said that "cares about the wealthy" described him very well. Now, 60% say that. In both experiments, specific information about his income increased that percentage. Compared to someone who saw no information about Romney, someone who learned that he had made millions of dollars in 2010 was 12 points more likely to say "very well" in the January survey and 10 points more likely to do so in the July survey.

We previously found that believing Romney cares about the wealthy is correlated with believing he doesn’t care about “people like me.” In this experiment, this correlation is significantly larger when told either about Romney’s income or tax rate than when told neither piece of information.

In the July experiment, we found that information about Romney's income (although not his tax rate) had this same effect.

What is the upshot here? First, on dimensions related to wealth and empathy, Romney is perceived less favorably than Obama. That's been the upshot of several of my posts with Lynn (e.g., here) and we will be updating that analysis soon. Other public polls, such as those of the Washington Post and Gallup, confirm this.

Second, specific information about Romney's wealth and income may worsen perceptions of him on these dimensions, but it is not a game-changer. As we noted in our earlier post:

The information about Romney’s income or tax rate did not affect how respondents evaluated Romney on other dimensions, such as his willingness to stick by his positions, his honesty, or his trustworthiness. It didn’t make respondents more likely to describe him as personally wealthy (most already do so anyway). And it didn’t change whether they believed he cares about the poor or middle class. When the information does move opinions, the shifts aren’t large. Many respondents may already have heard about Romney’s income or tax rate or simply don’t consider those facts germane. The Obama team may find that a campaign that implicitly or explicitly characterizes Romney as a plutocrat isn’t a slam dunk.

That's still true now, and it's worth keeping in mind when ads like the one linked above debut. At the same time, our experiments are just words on the screen during a survey interview, and may not have the impact of a political ad, with its richer palette of image and sound.

Third, even if Romney faces disadvantages on dimensions related to wealth and empathy, it's not certain whether those dimensions will be the most important ones in November. Empathy is not the one true key to victory. More important may be perceptions of which candidate will best improve the economy -- something on which Romney has the advantage.