Political scientists have long debated whether presidents can persuade people. George Edwards has amassed a vast array of evidence against presidential persuasion. Others, like Amnon Cavari in a recent paper, argue presidents can lead public opinion.

The latter view was boosted by polls that showed some movement towards gay marriage after Obama’s switch to support. However, Ryan Enos and Lynn Vavreck brought things back to earth a bit, showing that bumps and wiggles in support could be, well, just random bumps and wiggles.

Perhaps, though, the wiggles (not these guys) reflected something real, but we didn’t have enough statistical power to really know.

One way to further investigate the issue is to run survey experiments that randomly tell some respondents Obama’s position and tell the other voters nothing about Obama’s position on the issue. If those who hear about Obama’s position are more supportive of gay marriage, we could reasonably infer the president has at least some ability to influence public opinion.

We wouldn’t expect Obama to persuade everyone, as other research has shown that voters who like a president are the ones who are most likely to be influenced by that president. Those who liked Clinton were most influenced by Clinton on gays in the military, for example. (The logic is based on either signaling or psychological theories.) We therefore focus in particular on voters who support or relate to Obama.

We also were interested in how information might matter so first asked voters about Obama’s position on gay marriage. Respondents had four options: Obama always supported gay marriage, he has recently switched to support gay marriage, he has recently switched to oppose gay marriage and he has always opposed gay marriage. Knowledge of Obama’s position was pretty widespread. Sixty-five percent got the right answer. Twenty-six percent said Obama always supported gay marriage. (Two percent said he always has opposed gay marriage and 4 percent said he switched from support to opposition to gay marriage.)

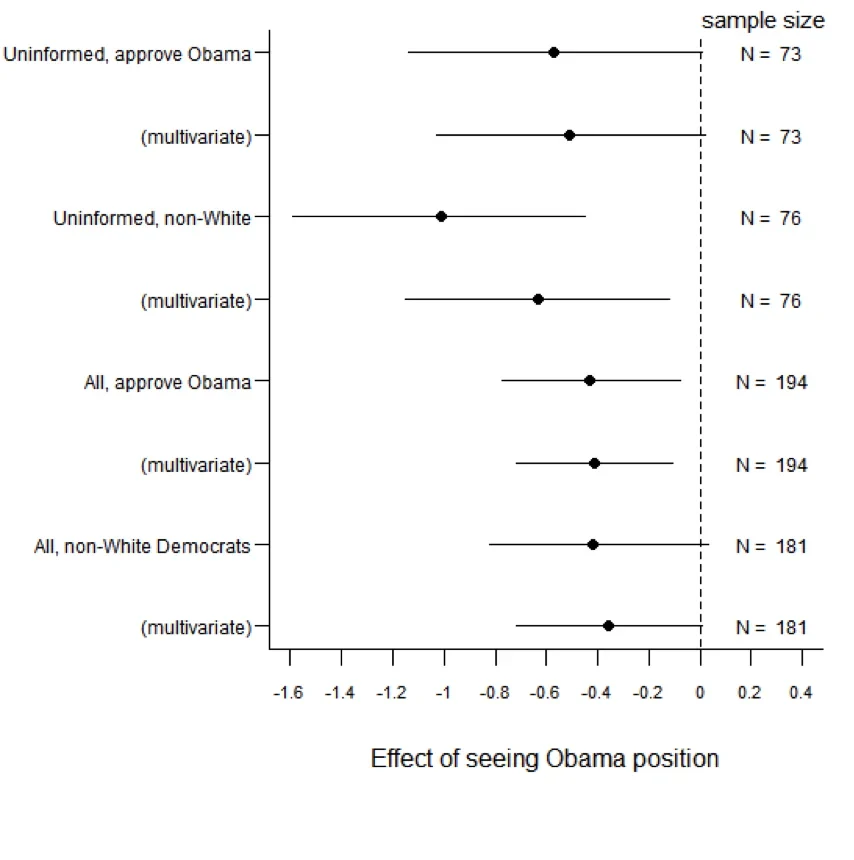

What we really care about is the effect of telling people Obama’s position on support for gay marriage. The figure shows the influence of the random treatment (being informed of Obama’s position – this was randomly determined and did not depend on whether the respondent already knew Obama’s position). I estimated a series of OLS models in which the dependent variable ranges from 1 (for strong support of gay marriage – 32 % of sample) to 4 (strong opposition to gay marriage – 31% of sample) . (Ordered probit yields similar results.)

First, I looked only at those voters who did not answer correctly about Obama’s position on gay marriage. What happens to those who (randomly) are exposed to Obama’s actual position? I looked at two categories of voters most amendable to presidential influence: those who approve of Obama and non-Whites. The figure shows the estimated effects and 90% confidence intervals from bivariate and multivariate analyses. (The multivariate analyses controlled for party identification, gender, church attendance and whether someone was born again. Since the treatment was randomly assigned and balanced on covariates, multivariate analysis is not needed to avoid bias, but increases precision.)

A negative sign means the random exposure to Obama’s position moved voters left (to be more favorable toward gay marriage). The signs in bivariate and multivariate analyses are all negative and the confidence intervals are mostly negative, especially for non-Whites. The sample size is small, so these estimates are not that precise, but they certainly suggest that information about Obama’s position increased support for gay marriage among these groups. There was no effect in either direction for Whites or those who do not approve of Obama.

I also estimated models where I ignored whether or not a respondent knew about Obama’s position and simply assessed the effect of randomly being told that Obama supports gay marriage. I broke things down in similar groups of those most likely to be swayed by Obama. The lines labeled “All, approve Obama” are the estimated effect on all respondents who approved of Obama. The lines labeled “All, non-White Democrats” are of non-White Democrats. Again, the signs in bivariate and multivariate analyses are all negative and the confidence intervals are mostly negative.

The bottom line? I would not close the door presidential persuasion. It is emphatically not a strong form of persuasion where Obama flips Republicans to support gay marriage. But it does seem to be the case that people who like or relate to Obama (informed or not) seem more likely to take his position after they see his position. In other words, the president can at least nudge those who like him to share his stance.

(I appreciate help on this from the Georgetown crew of Dan Hopkins, Jon Ladd, Jon Mummolo and Hans Noel.)