It’s hard to watch cable news shows nowadays without running into a segment on the role of racial prejudice in opposition to Obama’s presidency. On MSNBC, Keith Olbermann and Rachel Maddow are keenly sensitive to any remarks or actions that could be interpreted as race-baiting. The Fox News Channel, on the other hand, seems equally attuned to disconfirming these liberal charges of race-based opposition to Obama and his policies.

The debate that now wages so regularly through the cable airways echoes one that political scientists have been engaged in for decades over the role of racial prejudice in mass opinion. One group of researchers has consistently argued that a new form of racial animus—one that emphasizes a lack of black commitment to cherished American values rather than biological differences between the races—best explains contemporary white opposition to racially remedial governmental policies (see here). A rival school of thought, however, maintains that public opinion in the realm of race is “driven primarily by conflict over what the government should try to do, and only secondarily over what it should try to do for blacks” (see here).

There is evidence to support both sides of this debate depending on how we measure racial prejudice in public opinion surveys. “New racism” researchers typically gauge prejudicial beliefs with a “racial resentment scale” that taps into hostility towards African-Americans by asking respondents how strongly they agree or disagree with statements like “blacks could be just as well of as whites if they only tried harder.” When measured this way, racial prejudice is not only the prime determinant of white Americans’ opinions in the realm of race but an important predictor of their party identifications and presidential vote choices as well. Critics, however, contend that this racial resentment measure confounds anti-black animus with ordinary political conservatism, so that its strong political effects may only reflect adherence to unprejudiced ideological principals. These researchers therefore assess racial prejudice with more direct questions about African-Americans. It turns out that the political impact of prejudice is greatly reduced when anti-black attitudes are assessed with more blatant racial prejudice items. In fact, old fashioned racist attitudes like opposition to intimate interracial relationships were entirely unrelated to white Americans’ party attachments in the pre-Obama contemporary era.

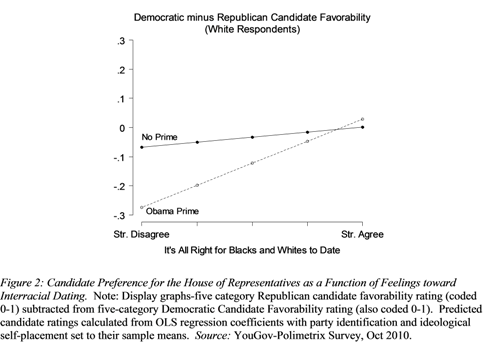

With Barack Obama the Democratic face of partisan politics in America, though, my research shows that more blatant expressions of racial prejudice are now significantly linked to white Americans’ party identifications after at least two decades of quiescence (see here). It is reasonable to suspect, then, that overt prejudice will also be more closely tied to 2010 midterm vote preferences than they were before Obama became his party’s leader. To test this conjecture, YouGov-Polimetrix asked a nationally representative sample of 1000 respondents last week how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “I think it’s all right for blacks and whites to date each other.” Since this question is also frequently asked by the Pew Research Center, I can compare the impact of on congressional vote intention in 2010 to its effect on 2006 vote choice.

The first figure below displays these relationships. Consistent with prior research, we see that support for interracial dating did not have a significant effect on 2006 vote choice for the House of Representatives. The 2010 vote intention line tells a much different story, though. Indeed, a change from strongly disagreeing that it’s okay for blacks and whites to date each other to strongly agreeing with the statement is now associated with 46 percentage point increase in the Democratic share of the two-party white vote.

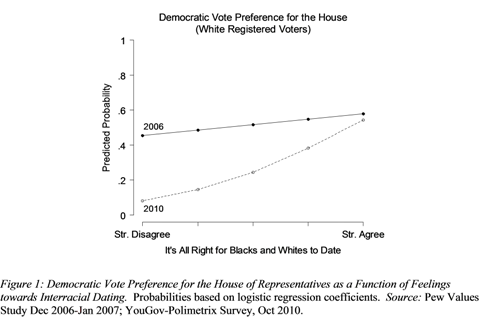

I also conducted a survey experiment to get a better handle on how President Obama’s strong connection to the Democratic Party helped produce the larger effects of racial prejudice on 2010 vote intention. After inquiring about how they intended to vote for Congress, half of my respondents were then asked (1) whether they wanted the new Congress to be more or less supportive of Obama’s agenda and (2) if an endorsement from the president would make them more or less likely to support the Democratic candidate in their district. Shortly thereafter, these same individuals were asked how favorably they felt toward the congressional candidates in their district. The remaining half of the sample, meanwhile, was just asked the candidate favorability items without being primed with questions designed to tie Democrats to Obama.

The figure below suggests that experimentally connecting Democrats to Obama does, in fact, increase the impact of racial prejudice candidate preference. After controlling for party identification and ideological self-placement, attitudes about interracial relationships were a statistically stronger predictor of Democratic minus Republican candidate favorability ratings among the subset of respondents who were primed with questions about Obama. In other words, it appears that blatant forms of prejudice, which had long been dormant in white Americans’ partisan preferences, will influence voting behavior in the upcoming elections because of Barack Obama’s association with the Democratic Party.