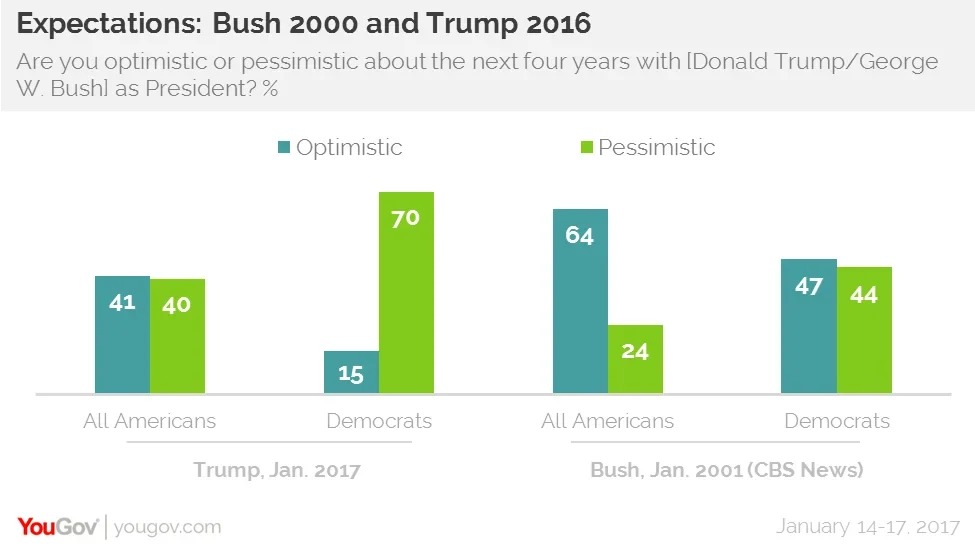

Americans, especially Democrats, are noticeably less optimistic about Trump's presidency than they were about Bush's 16 years ago

Even with the inauguration of Donald Trump just two days away, America has yet to come together in support of his Presidency. Previous election winners, even those who fought contentious election battles, won the support of a majority of the public soon after their victory. Majorities of Americans became optimistic about their presidencies, and their actions during the transition were generally approved.

Not all of those opposed to the incoming Presidents changed their opinion, though many did. On the eve of the 2001 inauguration of George W. Bush (like Trump, a Republican who lost the popular vote but won the Electoral College), Democrats were divided on whether they were optimistic or pessimistic about the next four years. But that divided Democratic opinion was enough to make optimists outnumber pessimists by more than two to one nationally. This year, however, Democratic pessimists outnumber optimists by more than four to one, and the country overall is divided about what they expect.

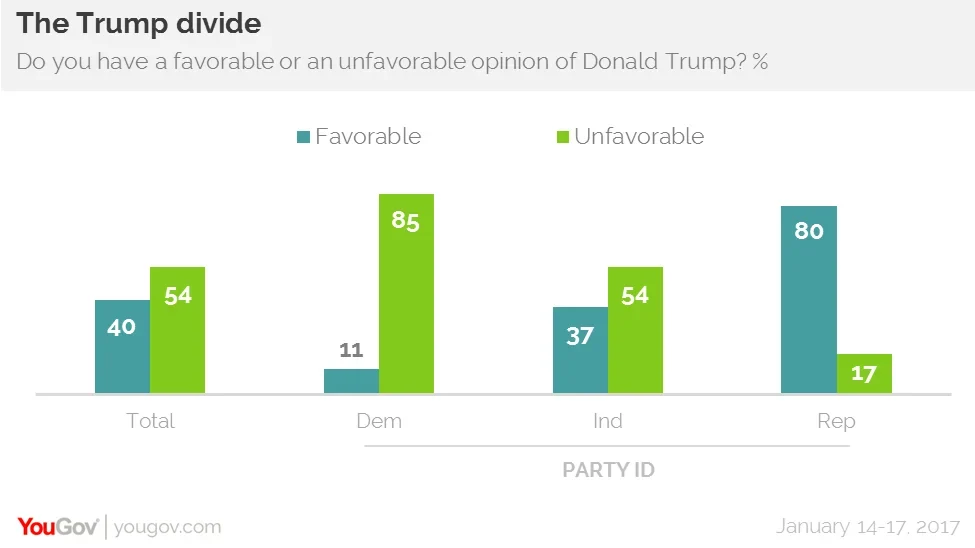

The same overwhelming party division occurs on question after question. Democrats and Clinton voters criticize nearly every act of the incoming President, something they did not do with previous Republican election winners. Whether this is due to a new Democratic intransigence or the combative President-elect’s own actions, the result is the same: Trump voters and Republicans are extremely supportive of their candidate, with high hopes for the next four years, while Democrats and Clinton voters remain extremely negative. Mr. Trump’s favorable rating remains well below 50% nationally, mostly because 85% of Democrats are unfavorable.

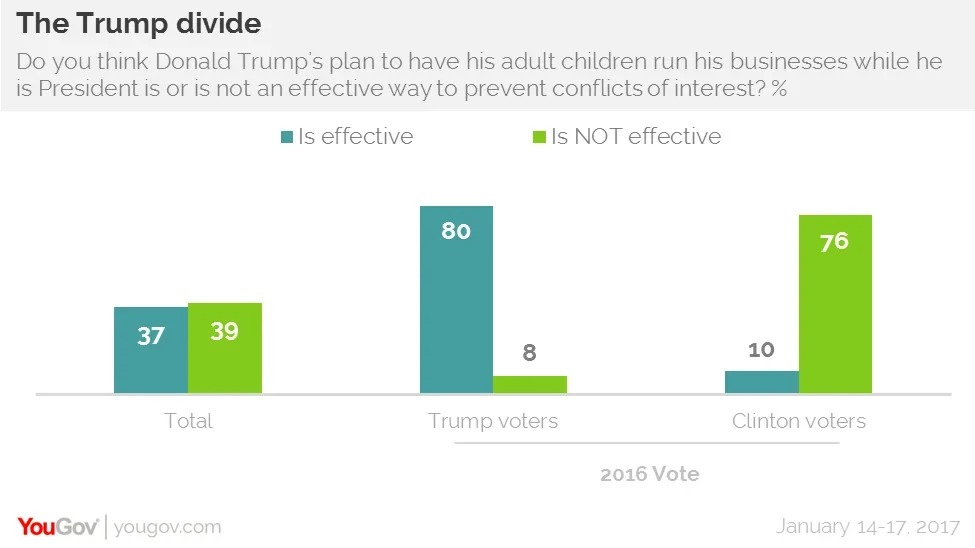

More than nine in ten Trump voters expect him to improve the economy; 85% say he will be able to improve America’s global image. Only 17% are even somewhat concerned about conflicts of interest in the Administration, something that worries a majority of the public overall. That is also true of opinion about whether turning over the Trump business to his adult children is an effective way to prevent conflicts of interest for him: by ten to one Trump supporters say it is effective, though the public overall isn’t so sure that will work.

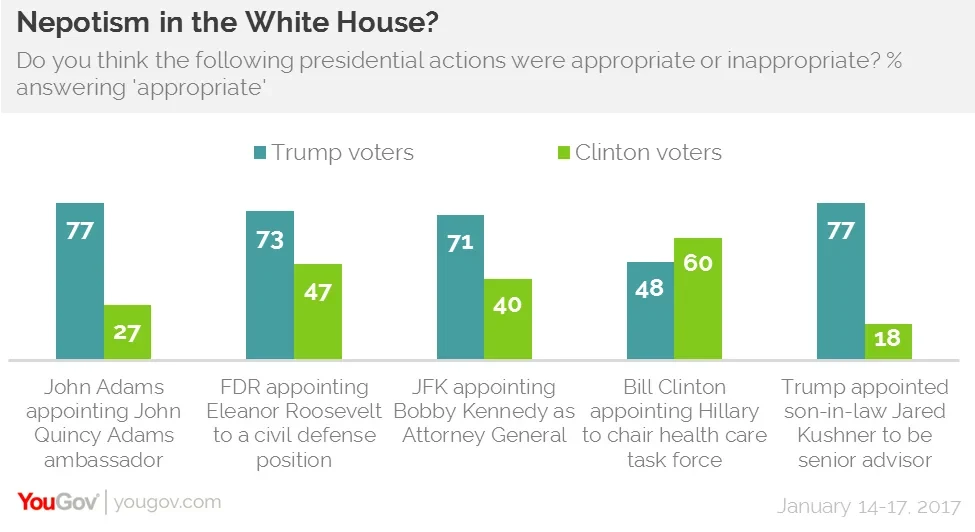

Trump’s announcement of the appointment of his son-in-law Jared Kushner as a White House senior adviser also split the public. But not Trump’s own supporters. They now give their approval to nearly every example of a President, Republican or Democrat, appointing a family member to a job. More than seven in ten say it was appropriate for John Adams to name his son John Quincy to an ambassadorship, for Franklin Roosevelt to name his wife as assistant director of the Office of Civilian Defense, for John Kennedy to appoint his brother Bobby as Attorney-General, and for Trump’s choice of his son-in-law as a senior adviser.

Clinton supporters disapprove of Adams’ and Trump’s actions, and divide on Kennedy’s. While they think FDR’s appointment of his wife was appropriate, they do so by a smaller margin than Trump voters do. Only Bill Clinton’s naming of his wife to head his health care reform task force in 1993 gets majority positive reaction from those who voted for Hillary Clinton in November.

But Trump voters find President Clinton’s actions more than two decades ago appropriate too. In fact, by 50% to 15%, they believe appointing a close relative to a government position is a good idea (overall, Americans say it is a bad idea by two to one).

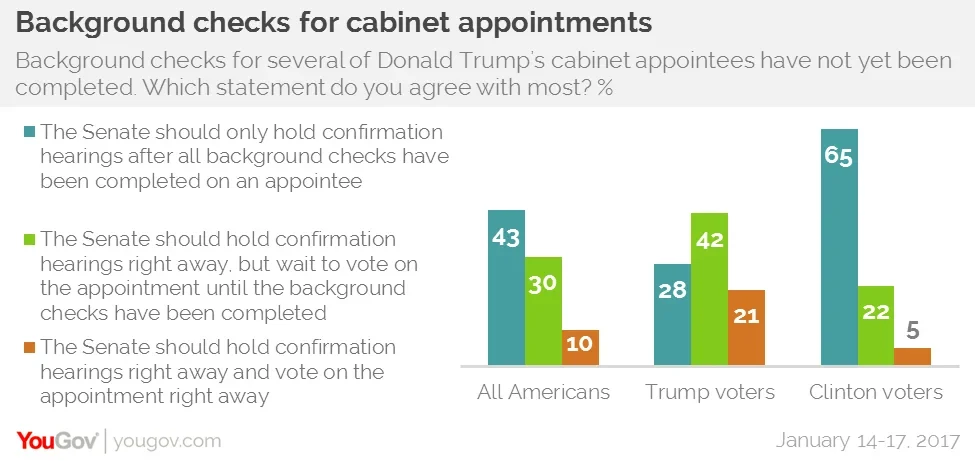

As for Trump’s Cabinet appointments, several of whom have yet to finish ethics and background reviews, 72% of Trump’s voters are not much concerned about Cabinet appointees not being completely vetted before their confirmation. But they, like most of the public, believe that background checks should be complete before the confirmation vote. Only 21% of Trump supporters say confirmation of a Cabinet appointee doesn’t need to wait for a background check to be complete.

In the last few days, Donald Trump has criticized polls that, like this one, have reported that American adults are not yet rallying around him as President. His skepticism about polls is not idiosyncratic. Historically, many Americans, politicians and public alike, have said similar things, although those with poor ratings may often be more critical. In last week’s Economist/YouGov Poll, 14% of Americans said they had no confidence in polls, even while they themselves were participating in one. Another 29% said they had little confidence. Democrats were more likely than Republicans or independents to say they had at least “some” confidence.

In a 1998 CBS News Poll, more than a third of respondents said that when they read or hear about polls showing one candidate ahead of another before an election, they usually think the poll is wrong. And that was much more often said by Republicans than by Democrats. At the time, Bill Clinton was enmeshed in the Lewinsky scandal, but maintaining high ratings in national polls.