Some liberal political commentators pointed to the racially charged debate exchange between Juan Williams and Newt Gingrich, in which the former Speaker of the House reiterated that African-Americans “should demand jobs, not food-stamps,” as the impetus behind his stunning come from behind victory in the South Carolina Primary. Or as Jesse Jackson put it in an op-ed last week, “Gingrich's campaign limped into South Carolina on life support. His revival came from his cunning peddling of a poisonous potion of race-bait politics to a virtually all-white electorate.”

Of course, those matter of fact claims had little basis in empirical evidence. So, did racial conservatism actually fuel Newt’s South Carolina surge? Prior political science research suggests that it might have. These “racial priming” studies show that subtle race-based appeals can be quite effective in activating racially conservative support for presidential candidates (see: 1, 2, 3, 4). I also speculated in my previous Model Politics post that Gingrich’s comments about African-American work ethic could be especially resonant in the current political environment because racial attitudes have a much stronger influence on support for Obama’s reelection bid than they had in the all-white contests of election years past.

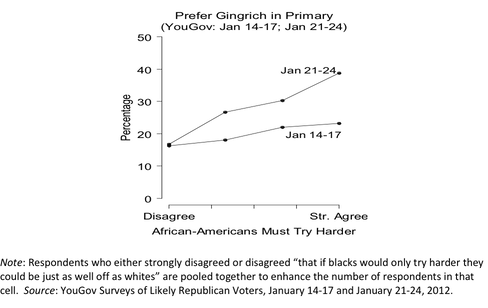

New survey data from YouGov is consistent with that contention too. Much like other polling agencies, Gingrich’s national support increased substantially among likely Republican Primary voters in a YouGov survey conducted after his January 17th debate exchange with Juan Williams. More importantly for our present purposes, the figure below shows that this enhanced over time support was most heavily concentrated among Republicans who strongly agreed with the following statement: “It's really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.” In fact, the figure discloses that Gingrich’s post-debate support increased by 16 percentage points among this racially conservative group, without any corresponding change among likely voters who either disagreed or strongly disagreed that African-Americans need only work harder to achieve parity with whites.

Yet, while the results presented in the figure are consistent with the notion that racial conservatism fueled Newt’s South Carolina surge, they are certainly not conclusive. For starters, there were less than 300 likely primary voters interviewed in each of the two surveys. Those small sample sizes necessarily limit the confidence we can place in the results. Moreover, racial conservatives may have flocked to Gingrich for other reasons, such as his forceful opposition to the “elite media” or because he is now positioned as the most viable alternative to the more moderate Mitt Romney. Regardless of the reasons, though, the results indicate that the most racially conservative Republicans have become significantly more supportive of Gingrich’s candidacy than their more racially sympathetic counterparts.