Last week, we asked a nationally-representative sample of YouGovers to tell us who, if they could ask any famous person, they would invite over for dinner. Rather than be given a prompted list of ‘likely’ invitees, we gave respondents total free rein over who they chose. Every famous person to receive more than four responses was included in the results.

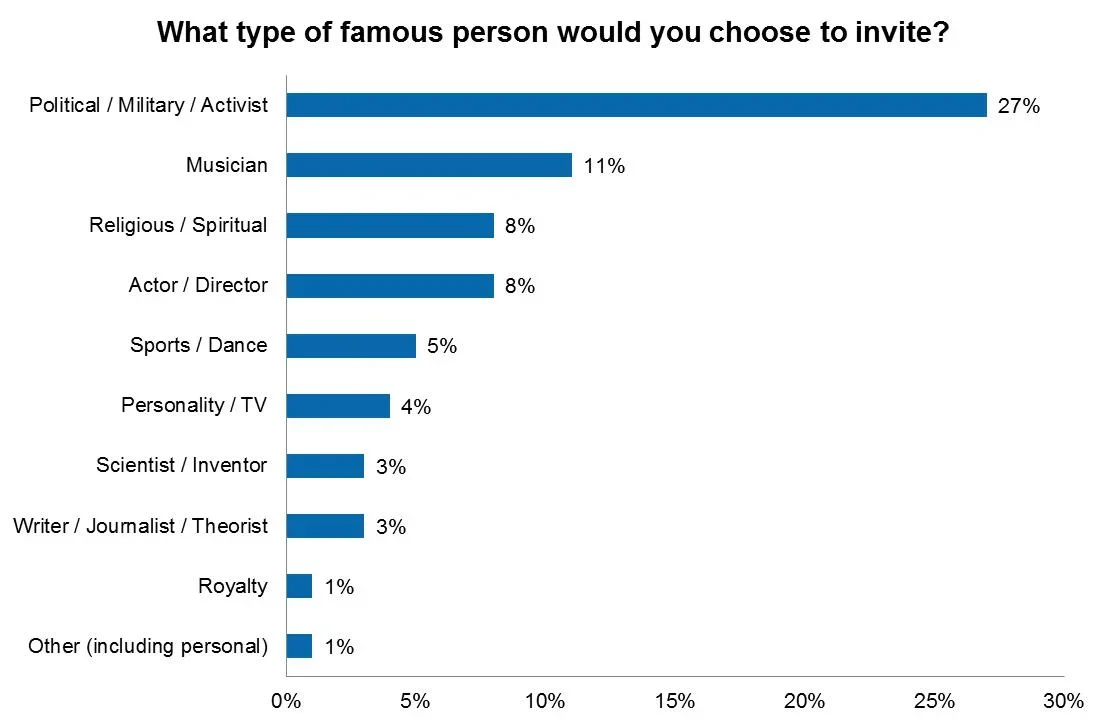

The results were startling – and clearly polarizing. Interestingly, though respondents could vote for absolutely anyone, around a quarter (27%) went for someone in politics, whether a current politician, military leader, or historical figure, which is perhaps indicative of the saliency of political issues in America today. Around 1 in 10 (11%) preferred to invite a musician, or someone in the music industry. Actors and religious figures were next most likely, at 8% each, following by sporting figures (5%) and TV personalities (4%). Writers, scientists and royalty featured next, with fewer again opting for this genre of dinner guest. As a great tribute to our loyal servicemen and women, a few even said they’d choose to invite some more personal figures – someone who had perhaps recently returned from Iraq or Afghanistan. An honorable dinner guest indeed.

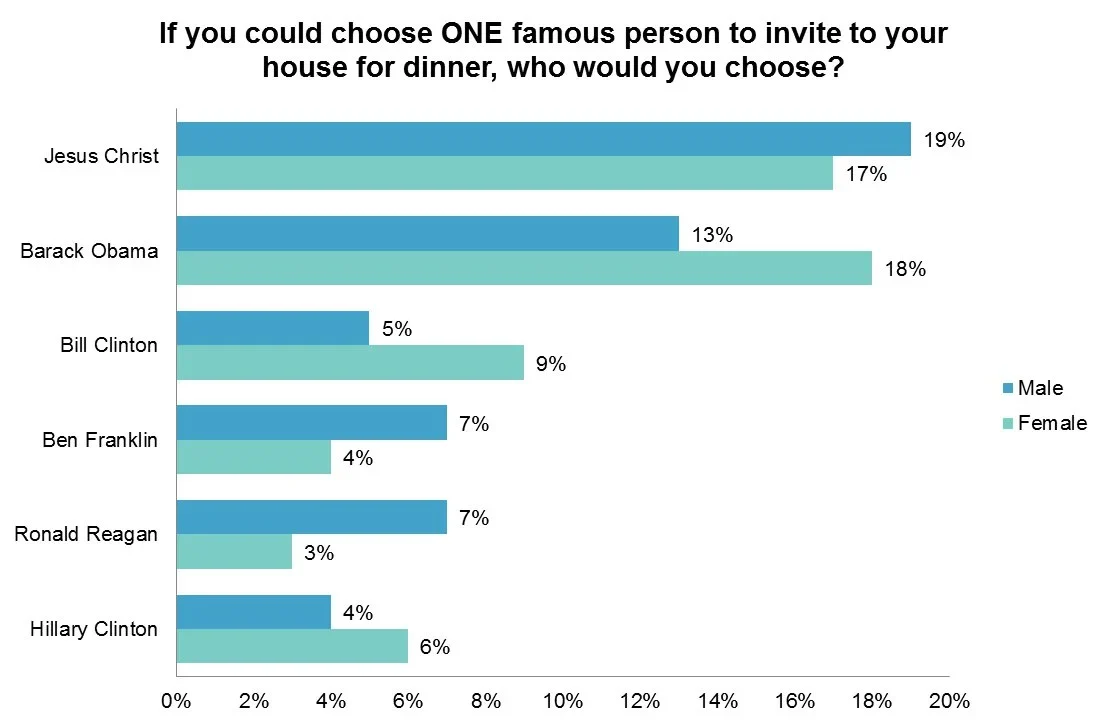

However, despite the category breakdowns, two names appeared overwhelmingly throughout our list of responses; two names which perhaps summarize the mood of the nation at the moment. The two names to feature most prominently in our survey were Jesus Christ and Barack Obama. Jesus Christ was the most popular, with 18% of the total, recalculated vote (after removing don’t knows and all those names with fewer than four responses) . Barack Obama followed closely behind with 16%.

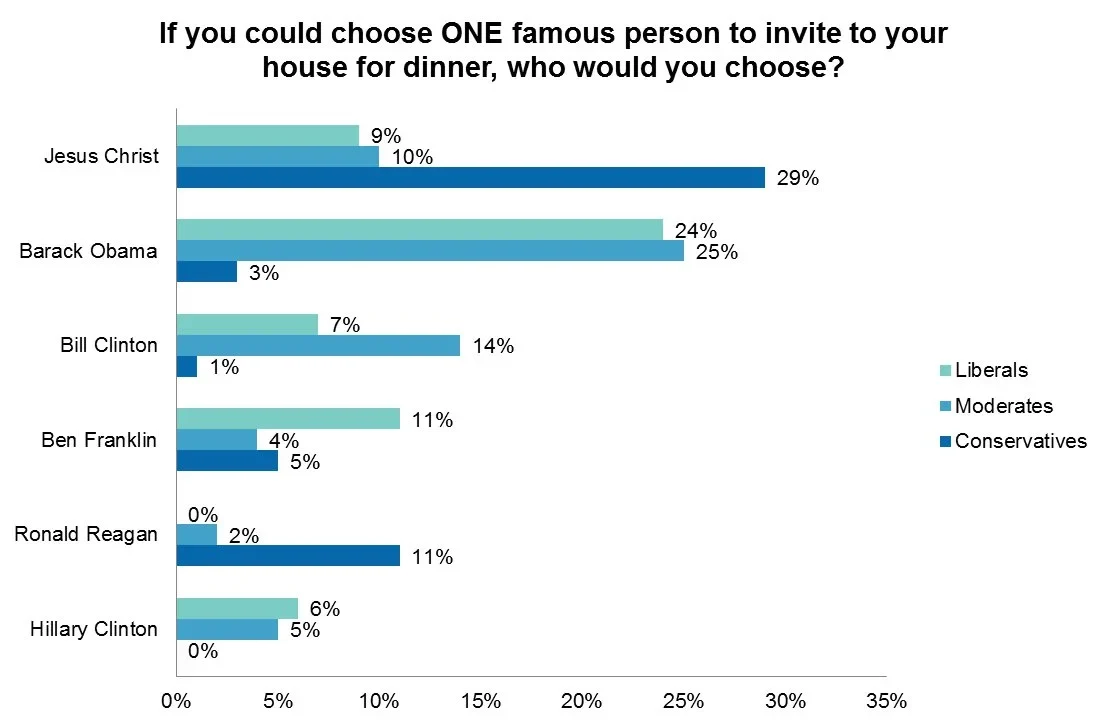

The most obvious distinction within these results, from looking at who was voting for whom, was clearly in relation to political ideology. We charted the top six results by each of the usual demographics (age, gender, region, household income etc.) and nowhere else did we see the distinction we saw here:

What’s particularly clear is that conservatives are overwhelmingly voting to invite Jesus, and liberals are overwhelmingly inclined to invite Obama – and moderates, in fact, follow a similar pattern to liberals. Looking at the other figures in the top six, some more polarizing choices become clear: liberals wouldn’t invite Ronald Reagan, but conservatives would. Conservatives wouldn’t invite Hillary Clinton, but liberals would. And Ben Franklin received a decent proportion of votes among all groups – as the ‘first American’, founding father, and pioneer of the original United States, it suggests his legacy resonates strongly among people of all ideological views.

Arguably the most significant distinction, however (though admittedly less pronounced), came in the form of the gender breakdown. Women were more likely than men to want to invite Barack Obama and Bill Clinton to their home for dinner than men, who were more likely to want to invite Ben Franklin or Ronald Reagan. On the surface, that distinction isn’t surprising, and isn’t even perhaps that shocking.

The gender gap in our dinner survey fits in well with recorded gender gaps in votes for recent elections: Bill Clinton and Barack Obama are the only two presidents to have recorded more votes among women than men. Last week’s Economist/YouGov voting intention poll put the Obama:Romney vote at 47:42 nationally. Among men the preference was almost indistinguishable (at 45:44); among women it was significantly more pronounced (at 49:40).

In an election, 9% of a female electorate could equate to roughly 6 million votes. In 1996 Bill Clinton beat Bob Dole by just over 8 million votes – arguably winning the election due to his popularity among women. As the only other president to boast such distinct favorability among female voters, the fact that Barack Obama is running for office again in November this year means that his popularity among women should not be ignored – especially in the wake of candidate apathy among Republican identifiers.

In the six decades following women’s suffrage, women were reported to be less likely to turnout at elections than men; since the 1980s this trend has changed. Rather than stay away from elections, it’s beginning to look increasingly as though women have the power to decide them.