Jim Warren’s weekend piece in The Atlantic about an annual meeting of political scientists and the research they presented had a provocative headline (not exactly what you expect your Google Alert to turn up when it emails you about a hit to your name), but it also hinted at “word of growing cheating on political surveys.”

The phrase “word of” suggested to me that the claim was more of a polemic than an argument, so I emailed Jim to ask if the scholars he referenced had any evidence that people were “cheating” on self-completed political surveys. They did not.

But I do, so I want to set the record straight. In July of 2011, I took a team of 8 graduate student research assistants to Las Vegas, NV to the CBS Research Facility called Television City in the MGM Grand Hotel and Casino. I hired 8 professional interviewers to conduct in-person face-to-face interviews and a small team of CBS staff to help recruit and direct research subjects to my experiment.

Doug Rivers, the CEO of YouGov/America, Inc. (the sponsor of this blog) and I wrote a short survey and trained the in-person interviewers on how to conduct the interview in much the same manner that federally funded surveys like the National Election Study or General Social Survey are conducted. YouGov, Inc. hosted the self-completed version of the survey.

The team recruited people passing through the area of the MGM Grand where the CBS exhibit is located and we randomly assigned 1, 010 people to complete the survey in one of two modes: with an in-person interviewer or via a computer (self-completed with no interviewer). The assignment to condition was done after people agreed to participate, thus there are no sampling differences, only a mode-of-interview difference.

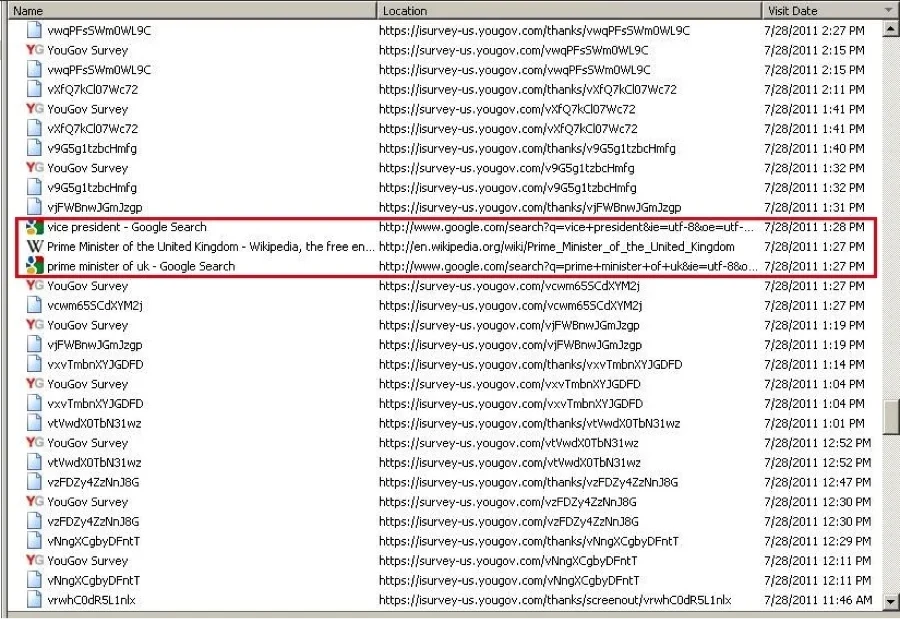

The results are interesting on a number of dimensions – more on that in a later post – but what I want to draw attention to now is how many people looked up (online) the answers to factual questions in the self-completed interviews. We asked questions like who is the Vice President of the U.S.? Or, who wrote Moby Dick? Some were open-ended and some had choices. In terms of politics we asked people to name (without any choices) the current V.P., to tell us who John Roberts is, and to name the Prime Minister of the U.K. (Incidentally, about 60% of our subjects could name the sitting Vice President without being given any choices. Only 16% could name the job Roberts holds.) We tracked cheating by downloading the browser histories for all the browsers on the machines after each interview (see inset below for example).

Of the 505 people who completed the survey on a computer, only 2 people cheated by looking the answers up on-line. That’s less than one-half of one percent of the respondents. This hardly qualifies as an alarming finding. Or as reason for “word” to spread of cheating on political surveys. Plenty of people had a hard time answering our fact-based questions, and they knew they were on the Internet, yet very few of them took the time to look up the answers --- in fact, almost none of them. And, one of the respondents who did look up the VPs name felt so badly about doing so, he came out and told us he cheated.

In the spirit of the popular television show Myth Busters, consider this myth busted! If others have evidence of actual cheating going on in self-completed surveys, let’s hear about them. Post links to your papers (or evidence) in the comments section below and we can have a dialogue, based on data, about whether this is an issue for survey research done via self-complete methods.

It is very easy to discount data generated via on-line surveys by saying people are “looking things up,” but in a slight twist on Tufte’s famous line: the absence of evidence does not give scholars license to say things that just “make sense” and “must” be true. Hunches are great. But my money is on the data. And the data show that people are not cheating by looking up the answers online.