The practice of judicial review has been enshrined in the American political system since 1803, when the Supreme Court in the landmark case Marbury v. Madison successfully asserted its authority to judge the constitutionality of laws passed by Congress. Nevertheless, the American public is surprisingly ambivalent about the principle of judicial review. Why is that? For people who pay little attention to politics, even central tenets of American democracy may be too hazy to earn unwavering support. But for many politically knowledgeable people these days, the problem is that the principle of judicial review is, quite simply, politically inconvenient.

Last week’s YouGov survey asked 1000 registered voters whether “The Supreme Court should be able to throw out any law it considers unconstitutional.” Only 48% of the respondents agreed with this statement (24% “strongly”), while 21% disagreed (8% “strongly”); the remaining 31% said “neither” or “don’t know.” Translating these responses onto a 0-to-100 scale, the average level of support for judicial review was a less-than-stellar 60.8.

Of course, the most important issue on the Supreme Court’s docket right now is the fate of the landmark health care reform bill passed by Congress and signed by President Obama in 2010. In a “baseline” survey completed last year, the same people who answered last week’s question about judicial review were asked their views about the health care reform bill. Forty-one percent said the bill should be repealed; 37% said it should be kept the same or expanded, while 22% said they weren’t sure.

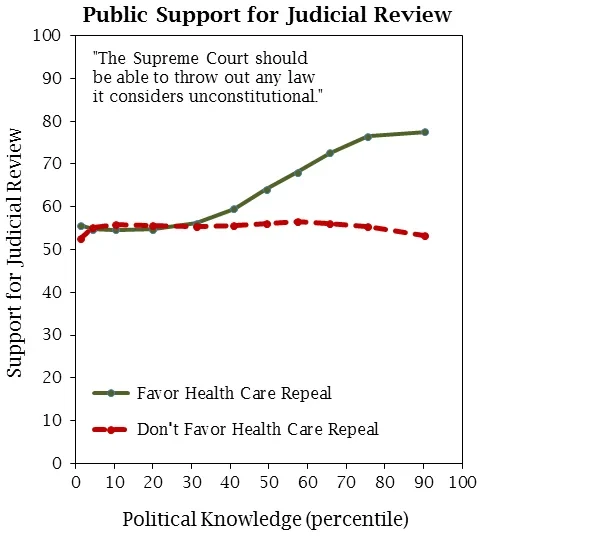

The accompanying figure (below) shows how support for judicial review differed between opponents and supporters of health care reform with varying levels of political knowledge. (People who said they weren’t sure what should happen to the health care reform bill are grouped with those who wanted to keep or expand it, and contrasted with those who favored repeal. Knowledge was measured by responses to a 10-item political quiz in the “baseline” survey, including factual questions such as what office John Roberts holds and which one of the major political parties is more conservative. The levels of support shown in the figure are smoothed to improve legibility.)

Among people in the bottom third of the distribution of political knowledge, views about judicial review were completely unrelated to opinions about health care reform; those who opposed health care repeal expressed the same middling support for judicial review as those who favored health care repeal. Presumably, these people were insufficiently attentive to political news to discern any important connection between the Supreme Court and Obamacare.

Among those who favored health care repeal, support for judicial review increased markedly with increasing political knowledge. This is not an unexpected pattern. Political scientists have long recognized that “Democratic beliefs and habits are obviously not ‘natural’ but must be learned,” as Herbert McClosky put it in a classic 1964 article on “Consensus and Ideology in American Politics.” They are more likely to have been learned by people who are sufficiently attentive to public affairs to know, for example, that John Roberts is a judge rather than a representative, senator, or cabinet member (54% of the YouGov sample).

What is more surprising is that there is no corresponding pattern of increasing support for judicial review among more knowledgeable people who happened not to favor health care repeal. While most of them were, no doubt, well aware of the fact that judicial review is a well-settled principle of American democracy, they are also likely to have been quite aware of the fact that the Supreme Court is currently contemplating overturning a landmark law that they prefer to retain or even expand. Faced with this conflict between principle and policy, they expressed only the same middling level of support for judicial review as less knowledgeable people did.

How much of the gap in support for judicial review among politically knowledgeable citizens is specifically attributable to differing views about Obamacare? After all, many of the same people who support health care reform have already been on the losing side of other momentous and politically charged Supreme Court decisions, including Bush v. Gore in 2000 and Citizens United in 2010. Thus, we might expect to find that broader partisan or ideological views contribute significantly to the gap. However, neither party identification nor ideology helps to account for differing views about judicial review among politically knowledgeable citizens once positions on Obamacare are taken into account.

Of course, many knowledgeable people who want to see the health care reform law preserved or expanded nevertheless did express support for the Supreme Court’s authority to declare laws unconstitutional. What distinguishes them from the people who could not bring themselves to endorse this temporarily inconvenient constitutional principle?

Men in these circumstances (more knowledgeable than average and opposed to health care repeal) were considerably more supportive of judicial review than women; young people were more supportive than older people; and people with more formal education were more supportive than less-educated people. When principles clashed with policy preferences, women, older people, and less-educated people were more likely to go with their policy preferences. All of these differences were nonexistent or much smaller among knowledgeable supporters of health care repeal.

Another item in last week’s YouGov survey sheds further light on differing reactions to the conflict between support for health care reform and support for the principle of judicial review. Respondents were asked whether “When politicians disagree, it is usually because there are good arguments on both sides of an issue.” Perhaps surprisingly, only 27% of the sample—and only 20% of knowledgeable opponents of health care repeal—agreed with this statement. Americans, it seems, are loath to interpret political conflicts as stemming from genuinely hard choices.

However, support for the view that there are usually “good arguments on both sides” was strongly related to support for judicial review among knowledgeable opponents of health care repeal. Indeed, those who strongly agreed were a whopping 35 points more favorable toward judicial review than those who strongly disagreed, even after allowing for the effects of partisanship, ideology, age, sex, race, education, and income. Apparently, a predisposition to see merit on both sides of contentious political issues played a substantial role in bolstering support for the inconvenient principle that the Supreme Court should have the last word on the constitutionality of Obamacare.

The importance—and the rarity—of a predisposition to see merit on both sides of contentious issues would not have surprised McClosky, who noted almost 50 years ago that “Compliance with democratic rules of the game often demands an extraordinary measure of forbearance and self-discipline, a willingness to place constraints upon the use of our collective power and to suffer opinions, actions, and groups we regard as repugnant. The need for such self-restraint is for many people intrinsically difficult to comprehend and still more difficult to honor. Small wonder, then, that consensus around democratic values is imperfect, even among the political influentials who are well situated to appreciate their importance.”