In the two weeks since the Supreme Court upheld Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA), journalists and pundits have scrutinized the public’s response. Most have found quite mixed reviews of the decision. For example, Pew reports divided approval of the court’s decision, with “disappointed” being the most common one-word reaction to the ruling. Given this, we wondered about more general evaluations of the court’s legitimacy since the ruling; especially in light of Larry Bartels recent post here at Model Politics.

The U.S. Supreme Court is a unique institution in American politics because it lacks explicit mechanisms to enforce its rulings (i.e. the “power of purse or sword”), relying instead on the goodwill of other institutions, and of the American public. This makes the study of Supreme Court legitimacy particularly important. Broadly speaking, the received wisdom in the scholarly literature on Supreme Court legitimacy is comprised of two, related observations: (1) the Court is perceived as above the “political fray” that characterizes the other branches, and thus enjoys relatively high levels of legitimacy, and (2) legitimacy itself rests on solid foundations, such as support for democratic values, and is thus independent of its decision-making as it relates to citizens’ partisan or ideological preferences.

However, a forthcoming article in the American Journal of Political Science (ungated here, summary here), co-authored by one of us (Christopher Johnston) and Brandon Bartels, concludes that legitimacy is conditional on perceptions of the ideological direction of the Court’s decision making. Specifically, citizens who see the Court as opposed to their own ideological proclivities confer less legitimacy on the institution than those who see the Court as ideologically congenial.

The recent decision by the Court on the Affordable Care Act offers an intriguing chance to reexamine the relationship between political predispositions, Court decision making, and legitimacy. Last week’s YouGov survey included two items utilized by past research to measure Supreme Court legitimacy, with responses ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree” (for ease of interpretation we convert each to a 0-100 scale):

1. “The Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics.”

2. “The Supreme Court can generally be trusted to make decisions that are right for the country as a whole.”

Given that the Court ruled in favor of the constitutionality of the ACA bill, we were interested to see how Court legitimacy would vary across Democrats and Republicans. Would Democrats show higher levels of legitimacy because of the ruling? Conversely, would Republicans show higher legitimacy in spite of the ruling, because the Court remains relatively conservative overall? Finally, does the pattern differ across levels of political knowledge, as suggested by Larry Bartels’ last post on the topic?

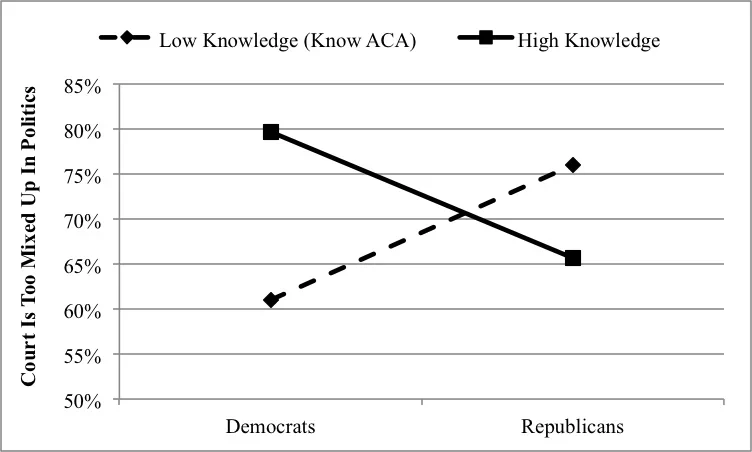

In the figures below, we show evaluations of the court conditional on party affiliation, political knowledge, and awareness of the ACA ruling.[1] The first figure below shows citizens’ perceptions of the Court as “too mixed up in politics.” Two points are immediately obvious: (1) citizens’ political predispositions matter for legitimacy, and (2) the way in which they matter is exactly opposite depending on political knowledge. For low knowledge citizens who were aware of the Court’s ACA ruling, Democrats are 15 percentage points less likely to think the Court is too mixed up in politics. For high knowledge citizens who were aware of the ruling, Democrats are 15 percentage points more likely to say the Court is too mixed up in politics!

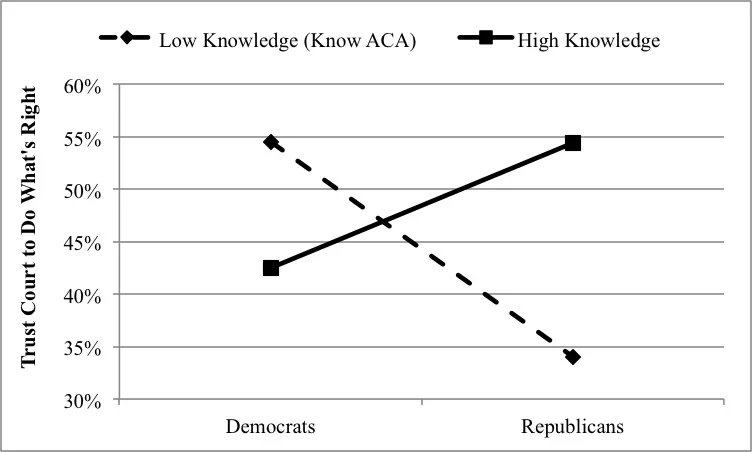

Looking at the second figure, which shows the results for the “trust in the Court” item, we see a very similar substantive pattern. For low knowledge citizens, Democrats were about 20 percentage points more trusting of the Court than Republicans. For high knowledge citizens, Democrats were 12 percentage points less trusting.

To summarize, in both cases, legitimacy varies across political affiliation, but in exactly opposite ways conditional on political knowledge. Why should this be? We believe the straightforward answer is that political predispositions do indeed shape judgments of Supreme Court legitimacy, but perceptions of Court ideology are what matter, not objective output per se. For citizens with generally low political knowledge, the “Democratic” ruling of the Court on ACA is a cue that the Court leans left, and thus legitimacy is higher for Democrats compared to Republicans. For generally high knowledge citizens, however, the ruling on ACA is seen as a less reliable guide to the overall ideological tenor of the Court. These citizens know the Court is generally right-leaning, and thus high knowledge Republicans show higher legitimacy than high knowledge Democrats.

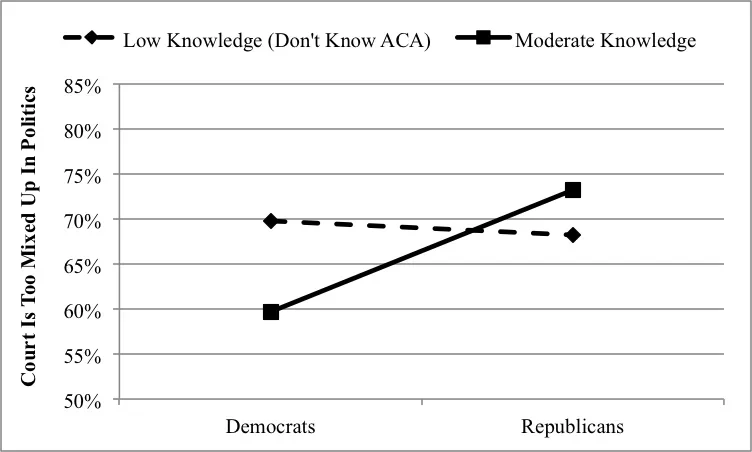

This interpretation is consistent with two further observations from the data, shown in the third figure below. First, among low knowledge citizens who did not know the direction of the ACA ruling, there is no difference in legitimacy between Democrats and Republicans. Second, the moderately knowledgeable (the middle 30% of knowledge), nearly all of whom knew the direction of the ACA ruling, show the same pattern as low knowledge citizens who did know the ruling. These citizens were exposed to the ACA and the cue it provides, but are again less likely than the very knowledgeable to be fully aware of the ideological direction of the Court considered across all of its decisions. It is only the highly knowledgeable that are able to look past this single, salient ruling, and map their predispositions onto the Court’s more general output.

To conclude: the present data support the conclusion that Supreme Court legitimacy is, to a meaningful extent, conditional on political predispositions as they relate to the output of the Court; however, what matters is how citizens perceive the Court’s output, and whether those perceptions are in line with their own preferences or not.

[1] The estimates are derived from a seemingly unrelated regression controlling for age, gender, education, race and ethnicity, and income. Political knowledge was measured with ten questions (e.g. office recognition of Nancy Pelosi). We divided knowledge into tertiles for the analysis. About 50% of the bottom third of knowledge correctly identified the ACA ruling, while nearly all of the top two-thirds correctly identified the ruling.